Review by Carter McKenzie

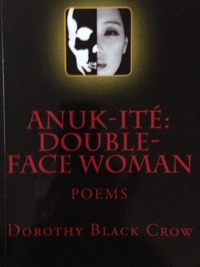

Anuk-Ité: Double-Face Woman, Poems

By Dorothy Black Crow

Turnstone Publishing (Corvallis, Oregon)

ISBN: 9781479338580

2012, 39 pp., $9.90 (on Amazon)

dorothyblackcrow.com

The poems in Anuk-Ité: Double-Face Woman by Dorothy Black Crow demonstrate the skill and wisdom of balance; through deft understatement they achieve the resonance of cumulative effect: they are weavings of one who knows how to reach into potent mystery “steady not pierced / by the black barb.” (“Double-Face Woman”)

The poems in Anuk-Ité: Double-Face Woman by Dorothy Black Crow demonstrate the skill and wisdom of balance; through deft understatement they achieve the resonance of cumulative effect: they are weavings of one who knows how to reach into potent mystery “steady not pierced / by the black barb.” (“Double-Face Woman”)

Manifested through the physical and spiritual worlds, and informed by Lakota history and legend, these poems honor and explore the possibilities of familial interconnection even as they expose betrayals of a people. With the exception of one well-placed villanelle, the poems are narratives. They all bear witness in memorable ways both to a Lakota history of suffering and to the authority of survival and renewal. In the light of carefully crafted language, silence becomes fiercely active: omissions become revelations.

In “Marriage Proposal at Branding Iron Creek #1,” the dwelling place consisting of a “metal cot beyond the black / iron woodstove” is marked by the violence of the past, an “M-16 bullet hole / clean through the foot-wide cedar log.” The understatement of the second stanza, “ ‘They got their man, Peltier, in jail,’ ” in its reference to the 1975 Pine Ridge shootout and to the injustices that preceded and followed it, only deepens the impact of the scene created in the first stanza. Yet details in this poem also reveal the care of the past: “the faint glow of whitewashed log / cabin walls axe-planed smooth long ago.” And, although “old vision pits / crumble in Badlands shale” in the surrounding land, the calls of Spirit owls persist. The speaker identifies herself as having been an outsider to this world in the poem’s epigraph “Can I Live Here?,” as well as through the context of the poem that precedes this proposal, “Christmas at Upper Cut Meat.” That the answer to her question is affirmative is shown in what she notes beneath the spider webs over the open door: “red tobacco ties still bless this place.” Spiritual power actively recalled through attentiveness makes possible inclusive partnership.

Central in Anuk-Ité are poems of recovery and transformation through prayer. “Wind Cave I: Inside Grandmother Earth’s Lungs” and “Wind Cave II: Time of Emergence” evoke the Lakota creation story of their Buffalo Nation, and the shape-shifting power of recovery. The first poem concerns appropriation that disconnects the cave from its spiritual meaning for the Lakota of being the first people’s entryway to the earth’s surface. Here, the Black Hills journey into the interior of the famous Wind Cave is no more than voyeuristic tourism, unconscious violation for the sake of curiosity. The entry is a door “blasted” in the side of Grandmother Earth, and the cave is “songless, / speechless.” Those who wander into the cave do so without reverence: “Like a virus / we swarm the lungs, / creep past the silence…penetrate / dry air pockets” where there are “no / air sacs / left; / nothing.” Lack of attention to the sacred in this context has taken away the breath needed for the vitality of a people’s place of origin. In this poem, loss of vision is the loss of the entryway to the sacred center’s mystery. The lungs of the cave are lifeless.

In contrast, “Wind Cave II” resurrects the sacred power of place by remembering the stories of origin and disappearance, the buffalo that “sank into earth” after being slaughtered for their tongues, and who were said to have gone into hiding in caves, “waiting without grass, hooves / still in the rock.” The association of the earth and the buffalo with the Lakota people lies in a shared lineage “some say” exists: “the soft red rock… / is the blood of Mother Earth / is the blood of First People / is the blood of Mammoth Bison.” Regarding the Buffalo Nation, this speaker states: “When we rise up from the earth again / we will not need the stairs.” Certainty is declared through faith: “I know the Place of Emergence: / Center of All That Is— / this time, Wind Cave.” Consciousness of the sacred—recognition of what is possible in “this time”—becomes the location of the opening to the center that will hold.

The sharpness of details and subtlety of their placement throughout this collection of poems resemble the artistic power of quillworking that Anuk-Ité bestowed upon those women who dared to dream fiercely enough to withstand her gift, enabling them “to pull out all those designs / pricked in the night sky — / quilled whorls and stars —.” (“Double-Face Woman”) This poetry’s honoring of Native American wisdom is a gathering of voices that renews connection, sustaining an essential fire.

Reviewer Bio: Carter McKenzie’s work has appeared in a number of anthologies and journals. She is the author of the chapbook Naming Departure and a full-length book of poetry Out of Refusal. A founding member of the poetry collective Airlie Press, Carter teaches poetry sessions to children and adults in Eugene and in the surrounding rural areas and serves as a board member of Beyond Toxics. She lives with her youngest daughter in the Cascade foothills.

This is possibly the best poetry i have ever read of free verse. I say this because the majority of these poems touched me to the core. I felt i was with them in their world, and tasted their bitter-sweet experiences. If you care about Native Americans or are curious about their feelings and lives, open this book and drink in the words. You will never regret it.