Riddle, Fish Hook, Thorn, Key by Kelly Terwilliger

Airlie Press, Portland, OR

ISBN-13 978-0989579964

2017, 79 pp., $16.00

Reviewed by Anita Sullivan

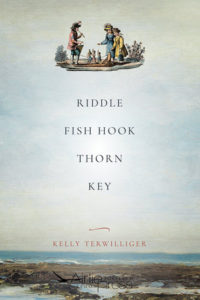

When you pick up a copy of this remarkable book, stop! Look at the cover – really look at it. Across the bottom rests a narrow strip of seashore in vivid blues, whites and browns. Above that, sky takes up the rest of the space. The ratio of sky to seashore is 5 to 1, which may resonate slightly in your vision as a very satisfying relationship. Yet the placidity of this image is interrupted near the top of the page by an odd little island with some old-fashioned people on it who seem to have no idea their small piece of ground has been detached from its own world and inserted into another one. Two distinct realities inhabiting a single place. Already, you might feel the center of your forehead humming with anticipation.

When you pick up a copy of this remarkable book, stop! Look at the cover – really look at it. Across the bottom rests a narrow strip of seashore in vivid blues, whites and browns. Above that, sky takes up the rest of the space. The ratio of sky to seashore is 5 to 1, which may resonate slightly in your vision as a very satisfying relationship. Yet the placidity of this image is interrupted near the top of the page by an odd little island with some old-fashioned people on it who seem to have no idea their small piece of ground has been detached from its own world and inserted into another one. Two distinct realities inhabiting a single place. Already, you might feel the center of your forehead humming with anticipation.

Then you read the title words: Riddle, Fish Hook, Thorn, Key. And the humming grows louder. If you squint a little and move the words around in your mind, you may recognize them as similar to an Anglo-Saxon kenning – an ancient word puzzle where certain words can be mixed and matched in ways that allow them to strike sparks off one another and reveal hidden meanings. For example:

king dragon

hall cave

- The king is a hall-dragon.

- The dragon is a cave-king.

- The hall is the king’s cave.

- The cave is the dragon’s hall.

Such simple word-sets formed the underlying structure of Anglo-Saxon riddles. Although the four words in Terwilliger’s title don’t fall neatly into this particular pattern, I feel them making a close quadrille with one another: A riddle can be a key, a fish-hook can be a thorn; a riddle can hook you, a key can pierce your heart. Thorn and Fish Hook stand between Riddle and its Key.

Throughout the book, true to the cover’s promise, these and other words shape-shift into one another in ways that are always surprising, but always completely appropriate to the underlying pattern the original magic formula has ordained.

The opening section, “Air” is also about water, about breathing and folding, taking in and letting out, jumping into. Entire poems breathe in as one thing, breathe out as another as when one sound shifts in a word/and summons another.

In “Handkerchief” the poet remembers a father, who sneezed and carried/this crumpled peony in his pocket.

Folding her father’s handkerchiefs, warm from the dryer, clinging together/like pages of a fragile book, she goes back to the flower image as she folds

soft square

halving and halving. What if I’d just kept going?

Blossoms unblooming, reversing

to a single point

with everything inside them.

In “Night Song” she feels her way into the longing of the owl’s call:

Not sorrow, but the overflow

of wanting to live, to break open

all those feathers into night …

The second section, “Body,” intensifies the theme of falling apart and coming back together to live again (which recalls the ancient enactment of death by dismemberment and burial as a rite of spiritual renewal).

The first poem begins big – imagining how a whale might die at sea:

turning softly within

to something like cream, until

the skin splits, the rest

falls away.

The poet then brings the whale body onto shore.

What then, strange coat. . . .

A hill of skin

enough to hide a house.

But the poem does not end there: a man rides down the beach on a horse; a group of people stand around the carcass, waiting for him. Where is the whale? Here on the sand, yes, but at the same time forever out at sea:

bones still falling.

I’m sure of it. Slipped from the skin

they descend through the sea’s green rooms …

Later in the section, in “Gift Horse,” the horse itself is now dead on the beach, like an old sail blown in.

The poet, looking at the horse, feels herself changing into an animal: I begin to wear fur. I feel hairs on my skin,/between my teeth, in every breath.

Half animal now, she reaches into the horse’s mouth, and behind the tongue/ that isn’t there, something jiggles./Riddle, fish hook, thorn, key –

Two more observations about this amazingly coherent and luminous book:

First, at the core of all the poems, whether there are people in them or not, is a steadfast and palpable love. The poet’s father is sometimes directly present, as are her two sons, and once they have been introduced, you realize they are, in some sense, inhabiting every poem. “Beyond Swans” begins

My friend once ate a swan,

the only thing she was ashamed to admit

she’d gladly do again.

And the poem, after immersing itself fully into the magnificence of this bird as cloud god, with its intimacy of weight, slips easily into a memory of the poet being tenderly carried as a sleeping child, up from the beach at night by her father,

He climbed up and over the rocks,

and my body felt loose and safe.

After which, turning back to the swan, she says

This is how I’d carry her

the one-who-ate-a-swan, who probably

never will again, whose burdens now

have changed their shapes, as burdens do.

Second, in my own reading of poetry, I especially look out for how much distance a poet is able to maintain between what she is trying to say, and what she actually ends up saying. If this distance is too close, the poem may feel “controlled,” and tend to be merely descriptive or informational. If the distance is too wide, the poem risks veering off into blind alleys of personal symbols or getting trapped in a kind of feedback loop of seductive images or sounds that have detached themselves from actual experience. In Riddle, Fish Hook, Thorn, Key, I believe Kelly Terwilliger has managed – partly due perhaps to her long experience as a professional storyteller – to maintain a perfect distance, thus allowing The Mystery to be doing its essential work to keep the poems honest, beautiful, and strange.

Reviewer’s Bio:

Anita Sullivan is a poet and essayist who has been part of Oregon’s literary community for 35 years. Information about her work can be found at www.anitasullivan.org