BOOK REVIEWS

Setting the Fires by Darlene Pagán, reviewed by Carolyn Martin

November 20, 2016Setting the Fires by Darlene Pagán

Airlie Press, 2015, $15.00

Reviewed by Carolyn Martin When Randall Jarrell defined a poet as someone “who manages, in a lifetime of standing out in thunderstorms, to be struck by lightning five or six times,” he could have been describing Darlene Pagán.

When Randall Jarrell defined a poet as someone “who manages, in a lifetime of standing out in thunderstorms, to be struck by lightning five or six times,” he could have been describing Darlene Pagán.In Setting the Fires, lightning strikes this talented poet dozens of times in poems that sizzle and smolder, delight and engage, surprise and move.

For starters, what is so striking about this collection is its structure. Pagán has adeptly arranged her forty-three poems into three sections– “Fuel,” “Heat,” and “Breath” – with fire, both literal and metaphoric, as the unifying image.

For example, the opening poem, “How It All Started,” immediately announces this intent. It tells the story of a female camper who has exasperated her male companion because she forgot the lantern, the towels, the hot dog buns,/the matches. She can’t fry an egg/over an open flame, dumps her companion out of a canoe into the river, and fails to extinguish the campfire. The last two stanzas contain the driving impulse of the collection:

Again and again,

she buried the stubborn coals, watched them

gasp for air and reignite. He slammed a car dooras an ember opened its smoking eye and trained it

on her like a dare. The ember woke another

and another as she turned to walk away.The stubborn ember of poetic imagination continues to open its smoking eye in such poems as “Wife Still a Suspect in Blaze that Claims Husband,” “Things I’ve Taken a Match To,” and “A Sage Advises How to Firewalk.” It morphs into the burn of desire in “St. Mary’s Catholic School for Girls,” “The Quarry,” and “Blackout.” It smolders in poems about loss and grief such as “The Uses of Grief,” “In College, I Job Shadow My Mother, A Hospice Nurse,” and “The Lamp.”

Setting the Fires, then, could easily serve as a model for how to structure a poetry collection, but it’s much more than that. A second and third reading – and this collection will lure readers back again and again – uncover a master poet who peoples her poems with unforgettable characters and imagery that pass the Emily Dickinson test: If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.

For example, in “St. Anthony’s Bread,” a chance – and initially uncomfortable – encounter on a bus results in a moment of communion between the narrator and a stranger in faded fatigues …/who lumbers down the aisle/with a yellow blanket tucked under his arm/like a baby he’s ransacked from a stroller.

He sits down beside the wary narrator, unwraps a monstrous sandwich, and, to her dismay, offers her a bite. Although his slick, black hair [is] speckled with crumbs/and woven with lettuce and His eclipsed eyes/give [her] vertigo, the narrator is engaged. She says,

… I do not flinch when

he tears off a chunk and extends

his open hand under my nose

as if I were a bird hovering

at the open window. I take

the bread in my mouth and hold it

like a promise, an offering, a secret

I will keep without knowing the terms.The beauty of this lyrical landing is one of the hallmarks of Pagán’s art: her ability to raise the poetry stakes from the concrete details of narrative to the heights of metaphor.

In “The Farrier,” one of the most touching and powerful narratives in the collection, a young girl contrasts her father – a blunt-edged shovel of a man. A dry/ spigot of a man – to the farrier: With his full beard/and chocolate gaze, he looked like a lean Grizzly Adams.

She observes how her mother curls her hair when this man is scheduled to come, and she listens to the whinnies of laughter emanating from the barn as her mother stroked the horses’ manes and the farrier/cradled one, then another hoof, his voice milky.

Since Dad is off working two shifts, the girl and her mother are left under the spell of a man so unlike him. The last two stanzas are filled with the girl’s yearning to have the farrier in their lives forever:

He greeted me with Howdy Do, Little Lady. I shared

the news that played all day and night from the barn,

like how it snowed in the Sahara Desert for thirty minutes

and gas prices were expected to hit $1.00 a gallon by summer.He searched my eyes the way only the horses did as he shook

his head and whistled disbelief. Just once, I wanted him

to sit down for supper, chew the fat, then ride the horses so

hard beside us, their shoes would wear out and he’d have to stay.While readers can commiserate with the absent father who is off supporting his family, they also can feel the burning desire for the connection and intimacy that the farrier provides. The narrator leaves us to wonder if Mom running off with the farrier would, indeed, make all the sense in the world.

Pagán fills out the pages of Setting the Fires with poems on topics like a failed driver’s test, a visit to a shooting range, knife-throwing lessons, death, the joys and heartbreaks of motherhood. She leaves us with so many memorable, well-crafted poems that readers will be hard-pressed to pick favorites. Lightning strikes every page.

Reviewer’s bio:

After forty years in the academic and business worlds, Carolyn Martin is blissfully retired in Clackamas, OR, where she gardens, writes, and plays. Her poems and book reviews have appeared in journals throughout the US and UK, and her second collection, The Way a Woman Knows, was released by The Poetry Box in 2015 (www.thewayawomanknows).

Nice and Loud by Lois Rosen, reviewed by Susan Clayton Goldner

October 16, 2016Nice and Loud by Lois Rosen

Tebot Bach, 2015, $16.00

Reviewed by Susan Clayton Goldner Nice and Loud, a collection of beautifully crafted poetry by Lois Rosen, is authentic and yet tender. It is intimate, unselfconscious and introspective. Her story takes the reader into the world of a young Jewish girl growing up in a cramped, Yonkers apartment after World War II. In the poet’s own words:

Nice and Loud, a collection of beautifully crafted poetry by Lois Rosen, is authentic and yet tender. It is intimate, unselfconscious and introspective. Her story takes the reader into the world of a young Jewish girl growing up in a cramped, Yonkers apartment after World War II. In the poet’s own words:Forever is how long our family will be stuck in that fourth-floor walkup.

Nice and Loud is inhabited by colorful and real characters. One of the most powerful is the writer’s father. He has cancer – a death sentence hovering over him, all the days of her childhood: . . .that bomb of my father’s possible relapse. Rosen paints her father in a way that balances the hard and the soft, and the reader finds him utterly endearing. But the dreaded cancer didn’t kill him:

One night he slipped into a diabetic coma/ the next day he was dead.

In one of my favorite poems, “Provider,” her father promises, You will be well provided for.

In the final stanza, Rosen says:

After the funeral we found bank books, bonds,

those dollars, we flipped through like cards,

screamed, clapped, giggled like hell,

our blouses soaked with tears.The author writes about an uncle who comes home whole from the war, in her poem “After the War”

He’d fought in France where Lanvin

created Arpege, Rumeur and My Sin,

where Bartholdi and Eiffel

designed Liberty, the statue

our family watched for a nickel

from the Staten Island Ferry,

my father holding my hand

where the ocean smell, gulls

and the view of Manhattan

belonged to us no matter

who we were.In this collection, Lois Rosen takes us to the profound place where language and emotion merge. The work is sometimes humorous, but always honest and hopeful. Read the book from start to finish and take this important journey with her. You will be far richer for the experience. Rosen’s first collection of poetry, Pigeons, was published in 2004 by Traprock Books of Eugene.

Reviewer bio:

Susan Clayton-Goldner’s poetry has appeared in literary journals and anthologies including Animals as Teachers and Healers, published by Ballantine Books, Our Mothers/Ourselves, The Hawaii Pacific Review-Best of a Decade, and New Millennium Writings. She is the author of a collection of poetry entitled, A Question of Mortality.

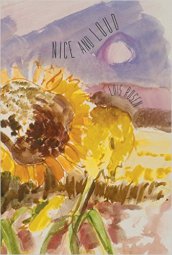

a question of mortality by Susan Clayton Goldner, reviewed by Lois Rosen

August 21, 2016a question of mortality by Susan Clayton Goldner

Wellstone Press 2014 $15.00Reviewed by Lois Rosen

I first had the joy of meeting Susan Clayton-Goldner at a novel-writing workshop led by Marjorie Reynolds in Portland, Oregon years ago. Susan shone as an astute critic and author of family-centered mystery novels. She’s published three: Finding a Way Back, Just Another Heartbeat, and Murder at Cape Foulweather. Since childhood, Susan has devoted herself to honing her craft. Besides being an award-winning novelist and popular blogger, she’s an accomplished poet whose work has appeared in literary journals for decades. This year, finally, her heartfelt poems have been gathered into her first poetry collection, a question of mortality, published by Wellstone Press.

I first had the joy of meeting Susan Clayton-Goldner at a novel-writing workshop led by Marjorie Reynolds in Portland, Oregon years ago. Susan shone as an astute critic and author of family-centered mystery novels. She’s published three: Finding a Way Back, Just Another Heartbeat, and Murder at Cape Foulweather. Since childhood, Susan has devoted herself to honing her craft. Besides being an award-winning novelist and popular blogger, she’s an accomplished poet whose work has appeared in literary journals for decades. This year, finally, her heartfelt poems have been gathered into her first poetry collection, a question of mortality, published by Wellstone Press.Breaking from convention, all the words in the title on the cover begin with lowercase letters. Perhaps Goldner chose this to symbolize mortality humbling us. A black background frames women in a dark room. Dressed in black with her back to the reader, the central figure seems turned from tragedy, as if Goldner wishes to escape agonizing memories, but forces herself to confront them. Beyond glass, grey sky reveals light breaking through.

In the poems as in the picture, there is a sense that tragedy has transformative effects. In the poem “An Eternity of Hope,” after a brother’s suicide brings pain like “broken glass,” hope does “simmer.” Her grief never disintegrates, but a daffodil poking up from “frosted earth” symbolizes beauty coming back like flames rekindled.

Death softens the poet’s heart, makes her more vulnerable, yet more empathetic. For example, in “When My Father Slipped into His Death,” Goldner writes:

Near the foot of his bed, I expect fear,

But the face and hands are too familiar.In a rush of lost affection, I uncurl

his fingers, pet a ruffled arch of brow…and the years of rage, too hot to touch,

cool at once into this mourning.The words “mourning,” “longing,” and “memory” echo through this book. Fresh images and powerful lines move the reader through profound experiences of love and loss. Regret, loneliness, forgiveness, fury, sadness—the many stages of grief recur. The book pays tribute to complicated, flawed but cherished family members who have died, leaving their survivor bereft yet determined to write these moving, elegiac poems honoring them.

Many of the poems employ nature and weather to convey inner landscapes.

But one season bleeds into the next

And what nurtures can also strip away.

Soon the wildflowers will

fold in their perfect petals and disappear

into the pine-scented earth.

Only their memory will flicker

across the quiet face of time.…pointing that bullet

toward the empty hole in yourself.In closing, I’ll point out a powerhouse poem: “In My Favorite Easter Memory of Lillian Nell.” She is: “Chanel # 5 and whiskey,” “stiletto heels,” “spider-leg lashes.” I won’t give away the poem’s stunning end. Read it and this whole collection for narrative poetry strikingly passionate, honest and profound.

Reviewer bio:

Lois Rosen’s poems and stories have appeared in over a hundred periodicals. Traprock Books published her poetry book Pigeons in 2004. Tebot Bach Publishers published her second collection Nice and Loud in 2015.

Avenida Uriburu by Michael Hanner, reviewed by Sara Burant

June 1, 2016Avenida Uriburu by Michael Hanner

Chandelier Galaxy Books, 2015

Available on Amazon.com for $6.00 plus s & h Reviewed by Sara Burant

Reviewed by Sara BurantPerhaps not coincidentally I was reading Avenida Uriburu on a train. It was raining steadily. Outside, shapes and colors ran together. I forgot where I was then remembered a jacket I wore as a child. Seeing the jacket that wasn’t there but curiously was, I regained my bearings: reading a book of poems situated in Buenos Aires on a train heading into Oakland, California. “Without images we tend to lose our way,” wrote James Hillman. Avenida Uriburu is a book concerned with images and bearings, with the extent to which one can and cannot orient oneself in territory at once familiar and strange. In lieu of compass and map, poet Michael Hanner both engages the art of noticing and constructs imaginative spaces, inviting gesture, object and persona to inhabit them.

Notitia is the capacity to form true notions of things from the act of attentive noticing. The word notice is related to the words connoisseur, incognito, recognize and gnosis. Each of these words finds resonance in this collection. In many of the poems the speaker is a connoisseur of the sensual, of red wine, chorizo, the scent of jacarandas, color and touch: “Opposites are sewn into your life,/buttons on a dress someone else/must button and unbutton for you./Hold still, they say; and you feel their fingers/moving behind you like butterflies.” Sensual experience is a kind of guide, leading the speaker to glimpse, at times even to inhabit, albeit briefly, the soul of the place.

Governing these poems is an intelligence which resists drawing conclusions. The poems are far more interested in alchemy, in the buzz and hum produced by the proximity of things. In the poem “La Biela,” for example, the speaker is sitting on or near the terrace of a hotel’s cafe, noting what he sees: “The ancient gum shades/the well-heeled diners and riffraff/sucking eggs and medialunas…” But more than that, he is pairing things, letting them rub against each other, creating a static effect. The poem goes on:

Before the entry is a fiberglass statue

of one of the race car drivers

who patronized the cafe

a half century ago

before people began disappearing

into the windy delta.

The whiff of dyed red hair, the chameleons,

the English spaniels sleeping under our feet.In just a few lines we receive a sense of the strangeness of the ordinary in Buenos Aires. The kitschy fiberglass statue of a pop-culture icon whom we imagine racing over open spaces makes way for the ghosts of those who disappeared into the windy delta in the last century’s political upheavals.

The speaker of another poem, “Avenida Ayacucho,” observes a man presumably a member of the Argentine elite: “The tan is flawless./The face has seen everything./The eyes so like a serpent,/impersonal as Switzerland, perhaps they are only cameras.” Implicit is a sense that by cunning, luck or complicity this man survived the terrible years of 1976-83. In Invisible Cities Italo Calvino notes, “The city, however, does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows…the poles of the flags, every segment marked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls.” In these poem we find enactments of Calvino’s observation. The past, including the dead and disappeared, not only hovers over but is woven into Hanner’s Buenos Aires.

As well, the poems often evoke a sense of precariousness and contingency: “Here in the south of the world/the power fails/in a city where I speak not the language./We could use the strange key the landlord gave us…/The door knob doesn’t move./The elevators are dead./The mountains hem us in.” Syntax inverts. The same chord plays over and over. Stasis and repetition become species of instability. This is not the first world, and the keys the speaker’s been given are not the right ones. Still, the poet recognizes a kind of kinship with the place through possible fictions, possible lives.

The prose poem The Window postulates a life in a nondescript slab of a building, the poem accompanied by an intriguing photograph of one such building, taken from the ground and angling up, rendering a sense of vertigo. The speaker of this poem lives incognito, resident or traveler, and watches with intense interest the only neighbor he ever sees, entranced by her watering the flowers: “In that entire space the only real color is the red of her impatiens.” Yet in the end this speaker cannot bear the pressure of being recognized, or rejected, and stays away from the window “like the other people who don’t live here.” The city invites and enthralls, and the city withholds. It is itself a kind of tango dance, choreographed by suggestion and nuance, as much by what is not there as by what is.

Again, Calvino provides perspective: “The traveler recognizes the little that is his, discovering the much he has not had and will never have.” Hanner deftly manages this tension. A wise traveler, he realizes his knowledge is limited: “Then Yesterday, vain and harsh, humped home,/dark falling, its work of not knowing/complete without knowing.” Gnosis is achieved but it is not an apotheosis of understanding, not revelation. It has to do with being open to sur/reality, experience whose fabric blends memory, history, dream, and the physical world.

The book’s final poem is an afterword, mapping the vicinity of Avenida President Jose Evaristo Uriburu. Whereas the rest of the poems seek to orient us psychically and emotionally, this last poem locates us spatially: “Two blocks one way is a shopping mall abutting Recoleta cemetery. Two blocks the other way is Avenida Santa Fe….” Rather than summing up the place, this poem allows us to linger with its familiarity, its laundromats, kindergartens, street vendors and grocery stores. We have been somewhere that seemed often strange, a place that offered pleasures and kept back potent secrets and pain that nonetheless bled from the bandaged wounds, a place “drunk with its own ooze and babel.” Perhaps we can never fully orient ourselves. The best we can do involves noticing and creating brief habitations. Our understanding is necessarily limited. These poems suggest that Buenos Aires is both unique and Everyplace, that what beckons and disturbs the traveler on the road, beckons and disturbs the traveler at home and is the condition of being alive at this, or any, historical moment.

Reviewer bio:

Sara Burant is the author of the chapbook Verge. Having temporarily relocated to the Bay Area to pursue an MFA in Poetry at St. Mary’s College, she looks forward to returning to Oregon and its vibrant literary community in 2017.

Ocean’s Laughter by Tricia Knoll, reviewed by Carolyn Martin

April 24, 2016Reviewed by Carolyn Martin

Ocean’s Laughter

by Tricia Knoll

Kelsay Books, Aldrich Press

Hemet, CaliforniaISBN: 13: 978-0692541852

2016, $17.00, 102 pages (on Amazon)

triciaknoll.com

twitter:@ triciaknollwind Those who know and love the Oregon Coast will experience a delightful shock of recognition while reading Tricia Knoll’s Ocean’s Laughter. This rich and varied collection about Manzanita – “an emerald of temperate rain-forest on the Pacific Coast ring of fire”– reveals a poet who has not merely observed nearly every inch of beach, type of sea life, and coastal weather event, but who – as a resident – has experienced them intimately for twenty-five years.

Those who know and love the Oregon Coast will experience a delightful shock of recognition while reading Tricia Knoll’s Ocean’s Laughter. This rich and varied collection about Manzanita – “an emerald of temperate rain-forest on the Pacific Coast ring of fire”– reveals a poet who has not merely observed nearly every inch of beach, type of sea life, and coastal weather event, but who – as a resident – has experienced them intimately for twenty-five years.The result is a virtual guidebook to the history and mystery of a world that is forever changing. In her poems and prose poems, Knoll engages us with stories and myths of “first people” (the Nehalem Tillamook and Clatsop tribes), the “discovery” of the Columbia River by Europeans, the 1700 earthquake and tsunami, and the current concern that “Part of the ocean’s depths are dying.” As she says at the end of her prose poem, “Mise en Scène – Manzanita, Oregon,” “Much comes and goes here.”

What remains consistent about this striking collection is Knoll’s ability to turn sharp observation into language that is precise, surprising, and musical.

For example, in the opening poem, “I Came Back Again and Again,” she recounts why she returns to the coast in lines that sing: to “hold a hand, fold a leash … hear my sump pump chuff … tickle sea anemones to squirt at me … bike the bay spit trail when scotch broom blooms.”

It soon becomes obvious that Knoll is a master of the list poem who revels in transforming piles of ordinary images into monuments celebrating everything from the City of Manzanita’s Lost and Found Department to shopping at a local store. In the latter (“As for Shopping”) we learn we can buy everything from bestsellers to Haitian metal work, from life jackets made for dogs to windsocks. What we cannot find, however, are things like diamond rings, gasoline, labradoodles, and parakeets. Beside all the expected and unexpected items that appear on shelves and all those that would be ludicrous to find, this poem is so much fun to read because Knoll has arranged all seventy-one items she cites in alphabetical order. We browse through her varied lines like shoppers looking for things to relieve the dreariness of rainy days – this area gets 70 to 90 inches per year – or to discover a small treasure we just can’t live without. The poem itself is one of those treasures.

Not only does Knoll delight in language, but also educates us about life on the coast. For example, we learn: “In winter winds,/umbrellas are useless./Bring a hat in all seasons, pull it down tight.” (“The Way the Wind Blows”) We are warned that “A child’s shovel is not safe/stuck in the sand overnight. Mornings/light up a new beach, handiwork/of the cleaner, scrubber, rearranger/of rootwad benches.” (“Pacific Night Work”) And in the inventive “The Child’s Sea Garden of Verbs,” she offers “a tidepool glossary” that parents and grandparents can “tiptoe through … to conjure in marine gardens repeating names like spells./Verb gifts of watch for sneaker waves and where you step.”

Interspersed among the poems are letters to government agencies that reinforce Knoll’s concern for the environmental issues. She writes to Oregon’s Governor Kitzhaber, asking him to “Please jumpstart an Oregon State Parks’ study about cars cruising on Oregon beaches.” (“Letter to the Governor of Oregon”)

The Manzanita City Council gets an earful. For example, she writes, “The City’s recent water bill asked for input to Council on local issues. Here I am. Begging again for driftwood awareness.” (“Letter #32 to the Manzanita City Council about Bonfires on the Beach”)

And,

The City Council did a fine job coordinating the Fourth of July parade today …. May I ask the City to require next year that vintage cars in the parade display signs identifying the make of the car and date of manufacture? … . Ask drivers to include exhaust emission numbers and the average mileage per gallon on highway and in-town driving … . You ask equestrians shovel up after their horses. Insist drivers own up to what autos leave in the ocean air. (“Letter #33 to Manzanita City Council”)

We can only guess at the contents of the first thirty-one letters! Undoubtedly, the Council was relieved to learn in #33 that this would be Knoll’s last letter. She was about to move.

At the end of Ocean’s Laughter, Knoll leaves us with poems addressing the sale of her home on Beeswax Lane and the bitter-sweetness of leaving it all behind. Anyone who has gone through the process of letting go of a cherished place can identify with the touching lines such as “My dog’s paw print carved in spring mud,/everywhere my fingerprints.” (“My Cottage Garden after The For-Sale- Sign Goes Up”)

And in “From Blue to Gray,” Knoll remembers:

Generations of children

have built dams in the outflow creek

at the foot of Beeswax Lane.

I cleaned St. Helens’ ash from the gutters.… Paid twice as much for flood insurance

as annual property taxes.

Three of the dogs I brought here

are dead. Mother’s ashes on Neahkahnie … .Few local poets are so committed to the art and craft of writing and so passionate about the health of the planet as Tricia Knoll. Ocean’s Laughter exemplifies both. What Sting – the songwriter, lead singer, and bassist for The Police – once said about his own artistic mission can easily define Knoll’s: “All my life I have tried to find the truth and make it beautiful.” Ocean’s Laughter is filled with an abundance of beautiful truths that will touch the hearts and minds of those who know the coast, and will serve as an invitation to visit to those who have yet to explore its rugged richness.

Author bio:

Tricia Knoll is an Oregon poet whose works appears in numerous journals and anthologies. Her chapbook Urban Wild (Finishing Line Press 2014) explores interactions between humans and wildlife in urban habitat ranging from Lone Fir Cemetery to downtown Portland. Ocean’s Laughter is available from Amazon and local bookstores in Cannon Beach, Manzanita, and Portland. Website: triciaknoll.com

Reviewer bio:

Carolyn Martin’s poems and reviews have appeared in publications throughout the US and UK. Her second collection, The Way a Woman Knows, was released by The Poetry Box, Portland, OR in 2015.