BOOK REVIEWS

Litany for Wound and Bloom by Judith H. Montgomery, reviewed by Catherine McGuire

April 29, 2019

Uttered Chaos Press, 2018, 80 pages, $19

ISBN 978-0-9998334-1-4

As I often do when I start a book of poetry, I opened Judith Montgomery’s Litany for Wound and Bloom at random and dove in. The poems are startling and beautiful, standing on their own even without the arc of the arrangement, though that had its own pleasing form.

“Listen” drew me in first, repeating some lines like a refrain (if the moon had been tatter and fog… if I lived in green valleys of wheat), making the unfolding story even more appalling, like a lullaby turned horror story.

In the three evenly-divided sections – (Womb), (Word), (Witness) – which concern motherhood – all the joy and the pain, especially in our violent world, I found many deeply moving poems, some difficult to read because the pain is so vividly communicated.

While most of the poems are free verse, they are consciously shaped: often couplets, triplets or quatrains, with clearly much thought given to shaping lines in complement to the content.

A poet works to make form, word choice, and sound fly under the radar as we read, and yet it is a big part of what makes a poem memorable. Throughout the book, Montgomery creates musical arrangements (if the moon had been tatter and fog rather than if the moon had been tattered and foggy) in what seems an effortless, but very skilled, technique of creating rhythms and music in the reader’s mind. A mother’s tragedy seems more horrific for being described in this elegant way.

The first section (Womb) speaks of the longing for motherhood, the failure to achieve it, the success at last which carries its own fear and wounding. The poems helped me, a childless woman, to get a better sense of motherhood. I am sure it will resonate even more deeply with mothers. But more than that, these poems speak to how life wounds all of us, often in a place we’re most vulnerable:

each scar’s a scarlet witness on or

in the body, inscribing its stubborn

devotion: Hurt. Hurry. Heal.

(“Yet Praise the Scar”)

The details of menstruation, ovulation, conception are presented in lyrical terms:

…one packed golden drop releases, lit seed

slipping down the sleek chute until that fortunate

fall into the womb’s open heart…

(“Apoptosis”)

Poems like “Expectant: I,” detail a different kind of anticipation and contribute to the deep exploration of this timeframe in many women’s lives. In addition, Montgomery explores this timeframe’s parallel to writing, summed up with the last line in this section: “All words uncoil to bloom in the womb of the poem.” Say that line out loud and you will hear some of the musicality this book contains.

The second segment (Word) concerns many different women, individually and in groups. It is in this section that the title of the book seems most appropriate, because this is indeed a litany of wounding and also the blooming of women, real and mythological. For example, in “Black Seed,” the poet describes Persephone in haunting and multi-sensory triplets interspersed by strong single lines:

My right hand, reckless, sought a second

flamed bloom, its dab of deckled gold, its

bottomless black velvet cup. Dragon-

flies were gilding river air…

The poems describing the poet’s mother’s descent into Alzheimer’s employ symbol and detail to move the experience beyond the mundane. In “Sometimes,” she writes:

An indigo cloak clasped at her paper throat,

my mother is stepping

deep and deeper into a mute forest wing-lit with

birds, a basket of seeds

clutched in her hand. Once in a while, she

remembers…

The last section (Witness) contains both poems of a deeply personal nature and those that touch on wider themes like war from a mother’s point of view. The section moves from a poem about a family’s pet burial ground to a courthouse where a teen is given into state custody to the speaker examining an oil painting about WWI. It links feelings of love and fear that mothers can’t separate. In “Bearing/Bearing Down,” the speaker says:

to be turned inside-out,

laid open for the universe to witness bairn emerge

from a body that was barren …

and in “A Blessing”:

… Child who

tore from my body, who blooms

now most beautiful…

The narratives in this section are gripping. “But You My Son” had me speeding through the first time as if it were a thriller. I was holding my breath as the nurse raced to the son’s apartment to try and revive him, not knowing if this poem was addressed to a living or dead son.

she gears through stop and flashing lights

to thrust the fail-safe key

into your apartment

lock, she bursts into the tossing dark

where the great factory

of your breath…

I appreciated the end-notes Montgomery provides as they give some background, and confirm some of my guesses, and also the acknowledgments. The latter offers a glimpse into the community of poets within which she works.

All in all, this is a rich collection of poems celebrating and lamenting women’s lives, with intimate glimpses into some of the deepest pain women endure, and full of vivid wonder at the miracle of birth, of life.

BIO:

Catherine McGuire is a writer/artist with a deep interest in Nature, both human and otherwise. She’s had four decades of poetry in publications such as New Verse News, FutureCycle, Portland Lights, Fireweed, andon a bus for Poetry In Motion. She has four chapbooks out: Palimpsests (Uttered Chaos) and three self-published (www.cathymcguire.com). She also has a full-length book of poetry, Elegy for the 21st Century (FutureCycle Press) and a deindustrial science fiction novel Lifeline (Founders House Publishing). A new chapbook, An Inner Quicksand, will be published next year by Finishing Line Press, and more short stories and Lifeline’s sequel are due out from Founders House Publishing.

The Moon’s Soul Shimmering on the Water by Doug Stone , reviewed by Erik Muller

February 25, 2019

Self-published book, 2018, 53 pages, $12.00

ISBN 978-1724418180

Available on Amazon and Barnes and Noble

To write 21st century poems in the manner of 20th century English translations of Chinese poems by Ezra Pound or Gary Snyder may seem an affectation – I use this word knowing that I, too, write this way. In Doug Stone’s second collection, however, the manner becomes a means to realize poems on important themes and to create a distinctly imagined world.

Here are many props of Chinese originals: lots of moon, a cup not a glass of wine, a hut, a well, fishermen, an old woman packing firewood, a small fire burning to ash. Central is the white-haired old poet, accurate to Doug Stone of Albany.

The question is, What can the poet make of such materials?

The book’s title suggests these are reflective poems, and the poet speaker is a fine companion through the changes of seasons and daily routines, even the impacts of war. He sits, gazes, sips his wine. He accepts calmly a scene that is not particularized by a local name, yet is specified by image:

Heavy fog has rubbed the landscape away.

(“First Morning of Spring”)

Thunder cracks like storm-snapped pines.

(“Catching Snowflakes in My Wine Cup”)

A brood of baby rabbits shiver in the rib cage

of a horse where his heart should be.

(“Another Battlefield”)

If you’ve read Chinese translations, you’ve felt a general effort at the calm unfolding of sequences that begin with external observation and move to the speaker’s state of mind, which is allied with the description. The three sections of “Autumn Reflections of an Old Poet” illustrate this, two of them beginning, “From my window.” The distant hill, which the poet describes in moonlight, is where he earlier wrote poetry, yet he now assures himself “new poems are just / another cup of wine away.” Watching crows for hours “preen away / crusted blood until they shine,” the poet wonders

What is it about my life

that I find beauty in a flock

of polished crows?

Sharing wine in the third section, he listens as his friend speaks of his wife:

Each time he says her name

something flickers in his eyes

like a flame wakened

in a bed of straw.

Friendship is a theme in the poetry Doug Stone emulates. The book’s last section makes a startling leap: it presents his original poems as an exchange between the great Du Fu and Li Bai. This is as daring as adding several more sonnets to the Shakespeare canon! The book has prepared for this to be credible, to complete Stone’s imaginative grasp of a world. Here are traditional moments in Chinese poetry: poems of parting, of reading the distant friend’s poems, of receiving the traveler’s answer, of recalling the long-dead friend while pausing at the sound of a death knell.

These poems sound accurate given what little we know of these poets’ friendship. Du Fu whispers his friend’s poems

to the willows who recited

them to the crickets, frogs, and nightingales.

How they sang the night alive with your words!

(“When I Read You New Poems Tonight”)

In straits, Li Bai reports, “My donkey skuffs a skiff of snow / for the last sweet blades of grass.” (“These Withered Autumn Wastes”) Years later, Du Fu laments his friend’s death, consoled by memories of youth spent together and by “the moon’s soul shimmering on the water, / the soul Li Bai was trying to gather in his arms.” (“Du Fu: On the Death of Li Bai”)

Doug Stone’s first book, The Season of Distress and Clarity (Finishing Line Press, 2017), supplied some of the strong Chinese-inflected poems included in the second. That book ranged across several of the poet’s interests. It touched upon Russian writers, U.S. cities, and desert and ocean – usually not part of Chinese lyrics. Close to home were the hard drinking and driving found in persona poems of his actual, though imagined, Albany. So, Doug Stone’s new work can resume any of these. Whatever material this poet elects to write about, he will surely use it in an imaginatively compelling way.

Biography

OPA Board member Erik Muller is a poet living and working in Eugene. His book of essays Durable Goods: Appreciations of Oregon Poets was published by Mountains and Rivers Press, 2017.

Before Dreaming: Poems by Arn Strasser, reviewed by Gigi Cooper

April 23, 2018Before Dreaming

EPSON MFP image by Arn Strasser

Budding Branch Books, an imprint of Asher & Merriman Publishers

ISBN# 978-0-9841874-1-6

2015, 89 pp., $19.95

www.buddingbranchbooks.com

Before Dreaming almost is correct; Between Dreaming would be accurate. Arn Strasser’s collection investigates the interaction between the dream state and wakefulness. He approaches the enigma of the dream world with both wonder and dread, exploring the boundaries between living and dead, youth and age, adventure and solace. Without magniloquence, he takes the reader on a journey from as close as the dining room and sofa to the markets and shores of Sardinia.

For Strasser, sleep is not a separate condition, but a way to access both memories and the future. Dream and memory inextricably intertwine in the book, most literally in the penultimate set of poems

called “The Wanderers.”

- Night

… so we may wander

the landscapes

of our dreams … .

these constellations of our

desires, a twilight of

remembrances.

- Awakening

… Do you hear

voices

of the dead,

who speak in memory … .

In this book, memories are more permanent than transitory life, but they are frustratingly unreliable and elusive. Several poems in the collection are lamentations — an effort to conjure and recapture that which is lost, which here is undiminished memories. The strongest poems are these first-person meditations.

I am trying, trying to bring you forward

even to see your eyes

but the song the song, I remember.

(“Your Irish Heart”)

Dreams in fact may substitute for memories. As for sleep, on the one hand, one suffers from an unstated fear of not waking (“A European Sets the Table”) from the dreams [that] are the dark energy of the night (“Silence Room”). On the other hand, the author looks forward to the repose of wandering, even though a dream is a creature of wonderment, longing and fear” (“Before Dreaming”).

Gardens, and fruit in particular, like dreams, serve as a mechanism for looking into the past and connecting to the present. “The Fig Tree” conjures a couple from “long ago”:

she feels the strength of truth

and when he hands her a fig

she bites deeply into the dark skin

Ripening fruit is a persistent theme, with poems featuring ripe plums, cherries, apricots, figs, olives, and apples. Ripeness is that perfect, ephemeral moment before a dream ends, before a memory fades.

While Strasser’s poems focus little on meter – and only one rhymes – he uses anaphora and refrain effectively and extensively, as in do not be afraid in “The Prayer.” The less compelling poems are descriptive landscapes such as “The Beach at Manzanita.” When tackling love, Strasser falters, verging on cloying recitations of emotions.

The “Three Tales” that close the book are a humorous departure. In the first, the writer worries needlessly over a cat. The second is a hilarious take on the contemporary preoccupations and proclivities of the Greek gods. Appropriately, the final poem finds an insomniac hotel guest sarcastically entreating boisterous Rome to keep him awake, ending the collection in a flourish.

Whether reflecting on a lifetime or invoking a generation past, the reader will not find answers here, but will find:

a tenderness, a kindness of

strangers, the milk of gracious

laughing, laughing.

(“Along the Path of Sycamores”)

Reviewer Bio:

Gigi Cooper is a transportation and environmental planner and writer in Portland. Her poem “Field” was an honorable mention in the Spring 2013 OPA contest.

Mrs. Schrödinger’s Breast: Poems by Quinton Hallett, reviewed by Alan Contreras

February 1, 2018 Uttered Chaos, 2015, 74 pages, $10

Uttered Chaos, 2015, 74 pages, $10ISBN 978-0988936645

Mrs. Schrödinger’s Breast is one of the most complex and carefully layered collections of poetry that most of us will ever read. I wondered, when I saw the title, whether this was a feminist restatement of Woody Allen being chased over the cinematic hills by a forty-foot mega-mammary. Hallett has a spiky sense of humor (in previous collections she asked Joan of Arc “what’s at stake” and had scientist Rosalind Franklin refer to DNA Nobelists Crick and Watson as “that base pair”), but I could not see her devoting poetic energy to such a project.

I then speculated whether Hallett, a noted gold-panner of human subtlety, had found some connection with physicist Erwin Schrödinger, whose hypothetical Cat that can be assumed simultaneously dead and alive has become well-known. Yes, it’s that Mrs. S., one Anny, apparently a woman of social vigor and marital flexibility. The poet’s connective tissue, set forth with glowing clarity in a short, moving “Afterword,” was her own potential cancer. This collection is built around potential: that which may or not be. A more macabre or less serious poet might have called the collection Cat Scan.

What Hallett has done is build a triple helix of her own experience, the life of Anny, and the theories of Erwin. This allows her to use the device of Erwin Schrödinger’s uncertain Cat, particularly for the many poems that are part of the main themes. We not only follow the unique circumstance of waiting for news of a biopsy in “Deadlock,” but we find frequent visions in these poems – sometimes in the path, sometimes in the mirror – of alternatives: things that may or may not happen, or exist.

Let’s look at “Deadlock” in its entirety.

Pre –

Under a tarnished sky, one moss-freighted limb

hunkers like a pathologist over the road to the lab

A petri dish is tonged from its stack

a left breast, unpowdered, awaits its probe

The pet cat wandered off a week earlier,

climbed into a box at the neighbor’s

Post –

The pathologist swivels her microscope

dice are in mid-roll, coin’s in the air

Results = Pending

Crest and trough

holding heavy the simultaneous upshots

The marked breast is carried to bed,

patted down under the press of blankets

The old cat’s dreamt alive

Regardless of outcome, every passage underneath

the laden maple will be a new snag in the chest

What weight on two words and a symbol: Results = Pending. These words are the mirror image of the Cat That (Is/Not) Dead, reflected inside the poet’s body. Results = Pending carries the weight of the potential of cancer on a yin-yang fulcrum – an equals sign, less than a word but in this poem so much more – in the center of the poem. The discerning eye might add a flickering arrow pointing each way.

This is poetic art at the highest level. It is the considered benchwork of a master crafter. Like a maker of swords, she adds how many layers? How many folds? How much flex here, and there? How many directions or outcomes? What will cause the balance to shift one way or another? I can’t help but think of James Merrill’s masterpiece “The Country of a Thousand Years of Peace,” in which … the sword that, never falling, kills … hangs over the bed of his friend, the Dutch poet Hans Lodeizen, whose pending death everyone in the room notionally denies.

How many of these poems are really about the mammiform protuberance in question? The answer – the uniquely suitable and beautifully surprising answer – is: it depends. It depends on the reader, in some cases. We find what we wish to find or are capable of finding. I may find something you do not, and vice versa. Hallett has always been a master of experience-oriented, multi-layered human life, both daily and profound. Here, we have at least two stories running simultaneously through a sizable, varied, and robust assemblage of poetry. Included is a series of poetic miniatures that refer more or less expressly to the titular breast, as well as some larger works.

There are other poems in this collection that allow us to sense that the Cat of Destiny is/isn’t in the room. Here is one of the Anny poems that do not have individual titles as they form a sort of bubbling rivulet flowing through the collection:

Anny Schrödinger has adventures

in marital architecture with Erwin and Hilde.

She/they are jealous or not jealous.

An affair or no affair? Without seeing the lover as lover,

there is no possibility of betrayal.

And another:

Mrs. Schrödinger’s breast has no standard cup size.

Is the cup half full or half empty?

Handful or sweaterful, a more fitting gauge.

To measure or contain is an insult

if volume is ever to be increased or diminished.

This particular poem recalls the late Hannah Wilson’s poem “The White Sweater” about a long-gone sweater that once may have overemphasized teenage breasts, but now, if replaced, might fit again because those breasts have been removed. Wilson, a friend of Hallett’s, was my high school English teacher forty-odd years ago: a circle quietly closes.

There is more to this collection than Anny Schrödinger or allusions to her husband’s invisible feline. When I first read through it, I thought perhaps all of the Schrödinger material should be in one section and all of the unrelated poems in another. Yet what, after all, does “unrelated” mean? We see many connections; some we may not see.

A few of the poems have a somewhat more casual feel to them, but a couple that seem a little too light at first develop a Merwinesque tone on careful re-reading. In these more delicate poems, there is someone in the whispering gallery; the ferns move in the breath of no wind. The collection includes poems written in a variety of layouts – I’m not sure “forms” is quite the right word in this context.

The collection begins with “Self-Portrait as a Bruise,” a poem that is not really part of the core “story” of the collection (or is it?), but which is such a precise, tightly wound coil of meaning that I will close with its last six lines here. (You’ll have to buy the book for the full experience.) This poem is one of Hallett’s all-time best, a garnet mine of meanings and ideas compressed into a single work.

Thumb-print or thunderhead,

my longing will never be taken

for love, though it is similar

in the way it uses quiet fury

to aggravate intention

and pools with me in one place far too long.

Quinton Hallett has always found good stories about us, as people, to share via her poetry. That’s true of many poets. Few take such care in folding their word-layers to make swords worthy of the title craft master. Such work is revealed to us in Mrs. Schrödinger’s Breast. Did I see St. Julian of Norwich, patron saint of cats, leaning down from her stained glass to have a closer read? Maybe. Felis ex Machina.

Also by Quinton Hallett: Refuge from Flux (2010), Shiver, Quench, Slake (2004) and Quarry (1992).

Reviewers Bio

Alan Contreras is author of the poetry collections Night Crossing and Firewand. His collection In the Time of the Queen will appear in 2018. He is co-editor of Birds of Oregon (OSU Press 2003), author of Afield: Forty Years of Birding The American West (OSU Press 2009), Northwest Birds in Winter (OSU Press 1997), State Authorization of Colleges and Universities and other titles. He is editing a collection of essays about Malheur National Wildlife Refuge and will soon begin work on a history of Oregon ornithology. He is a graduate of the University of Oregon and lives in Eugene.

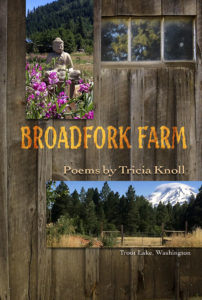

Broadfork Farm by Tricia Knoll, reviewed by Wallace Kaufman

January 1, 2018ISBN-13 978-0-9980999-4-1

The Poetry Box

2017, 73 pp, $12.00

On her web site, www.triciaknoll.com, Tricia Knoll speaks of herself in the third person. She is a tree hugging . . . Master Gardener who routinely talks to crows who ignore her. She also calls herself an eco-poet. In the opening line of “The Klickitats,” the first selection in Broadfork Farm, she says, I’m a farmsitter, once or twice a year, a few weeks. The farm is across the river from Mt. Hood and about 20 miles north near the village of Trout Lake. And there you have the setting and the character who inhabits these pieces.

In “Buddha Nestled in White and Pink Sweet Peas on the Fencepost at Broadfork Gate,”

Knoll says of the Broadfork Farm,

The farm is not for everyman.

In the old house, there’s no white sugar,

no microwave and when the first money

slapped down for land, no tractor, just a U-bar

digging fork with as many tines

as a March hare has fancies and that

was how it would be.

Those lines, like most of the selections in this volume, are the kind of free verse that could as well be prose. Expect no prosody here except for the thoughts and images broken into lines with no discernable aesthetic or logic. Perhaps read aloud by the author, the breaks would be justified by the reading; but this is a book, not a recording.

Two of Knoll’s pieces are written in traditional prose paragraphs, “Gloucestershire Old Spots” about visiting kids who are fascinated by pigs and “An Uncommon Prayer for the Farm,” which is more like a spoken hymn to the life and death, hardships and rewards of farm life than it is a prayer in any familiar sense.

What distinguishes these meditations about farm life and nature from so much contemporary “poetry” is their directness. Knoll does not struggle for novel metaphors. She doesn’t try to pass off obscurity as mysticism or intellect. She is almost always immediately intelligible. A reader can even learn a few lessons about animal husbandry and gardening.

The 37 poems in the 50 pages of text and photos are vignettes of farm life and surrounding nature. The photographs are nice companions to the writing, but not particularly good compositions or well reproduced. Together they capture the author’s love of the area and of this small organic farm that nourishes her body and soul.

Readers who know Knoll’s political writing – main line feminism and anti-Trump – won’t find it here. She writes in “Left with the Care,”

The banty rooster’s strident call

is light years from grinding war, spinning news,

suspicions of sects and warring politicians.

Broadfork Farm is her retreat from all that. Or, as she concludes in “An Uncommon Prayer for the Farm,” it is Repair of gratitude.

Urban readers will find here a usually gentle window into a certain kind of rural life. It may inspire the desire to get “back to the land” that inspires so many Woofers and some refugees from high stress jobs.

—————————–

Reviewer bio.

Newport writer Wallace Kaufman has written several books, including Coming Out of the Woods (Perseus Books), a memoir of 22 years in a North Carolina forest. He is an award-winning science writer who has published poetry in the US and England in magazines that include Encounter, Agenda, Carcanet, Oxford Today, and Carolina Quarterly. His fiction has appeared in Sewanee Review, Encounter, Redbook, Mademoiselle, and North American Review. His latest book is FOXP5: A Genomic Mystery Novel (Springer International, 2016) co-authored with astrobiologist and biomolecular engineer David Deamer. He recently taught Poetry for Everyone at Oregon Coast Community College.