BOOK REVIEWS

My Kindred by Paulann Petersen, Reviewed by Melody Wilson

January 19, 2024Reviewed by Melody Wilson

My Kindred by Paulann Petersen

Salmon Poetry, 2023

Available: Powell’s Books, Broadway Books, Annie Bloom’s Books, Amazon

Paulann Petersen’s My Kindred might seem to be about family, but it’s much more. The book invites us into a much broader exploration. The first poem, “Inhabited,” teaches us how to read the book beginning with an image of the speaker’s eyes imprinted by the vein-tracery of a maple’s leaf-children. We imagine veins in the speaker’s eyes, arms outstretched into limbs, hair leafing. Owls populate the limbs and by extension its sister, the poet, who moans, then creaks. The tree/sister/poet’s ear reverberates with all of nature.

“Inhabited” establishes the breadth of My Kindred while invoking the muses. But the reader becomes the muse, a collective muse rather than the traditional version. The invocation, appears at the precise center of the first page:

What to do, but invite them all

to come and live

here, inside me?

The second poem, “First Task,” prepares us for the journey with the speaker sweeping fallen blooms from her porch along with her illusions, creating

…an openness

Ready for a next spent bloom

to fall. An emptiness

where I can place my feet.

The action is both domestic and spiritual. And like an anchorite or a homemaker, the poet prepares us for the third poem in the book, “My Muse.”

“My Muse” begins with an epigraph from Heiltsuk tradition that reads:

––A wolf does not appear to us

unless it wants to tell us something

The Heiltsuk culture has its roots in British Columbia, an apt antecedent for the opening of the poem:

On the Alaska Fur Shop label

inside each jacket, stole, and cape

my grandfather made,

a she-wolf lived.

Then…

When I finally began to write poems,

she told me…

To what I make, she is sister.

She and my poems speak the same tongue.

The reader pictures a child in her grandfather’s shop. We imagine the label: pointed nose, ruff, the child’s thumbnail ticking over tiny gray stitches.

The poems in this collection effortlessly trace the poet’s catalogue of kindred—wolves, trees, owls, raptors, readers, women, all sisters in this beautiful, open-hearted explication of a sliver of world by a poet with nothing to prove and a great deal to share.

But there’s another kindred as well. Petersen’s literary kindred. Some of these literary kindred are mentioned by name, others lurk between the lines, but they forge a common language, an ambience that binds the book together.

For example, Anaïs Nin provides the epigraph to the poem “The World After”:

––Surely our parents give birth to us twice,

the second time when they die.

Petersen opens the “The World After” with My second birth comes parceled out/in two halves.

In this poem the speaker finds herself an adult without parents, a common event and one we see sometimes in poems, but it’s the close of the poem––I stand alone. Too new, too raw/even to fill my lungs/and let loose/a first cry––that is particular to Petersen. The interpretation of this essential loss is viewed from the position of a child even though it’s experienced as an adult. Being orphaned, even as an adult, is as much a separation as first birth.

A few poems later in “My Parents’ Ashes,” Petersen describes the remains of her parents after cremation with even more honesty,

Mostly they’re dust…

…a powder

that muffles every gleam—

one intent on taking to the air

and flying away into nothing.

Despite the parents’ importance, they are intent on flying away into nothing. The poem becomes even more visceral when we picture, in the speaker’s palm, their tangible remains, bits of bone./Chips. Nubs. Tiny beads. The speaker identifies these remains as sacrum, the bone she says is least likely to burn. Petersen uses that traditional belief by applying it to the Words on this page, which she instructs to:

…carry

My father and mother, my Whitmans.

Be the seeds that remain

when burning is done.

Be sacrums, too. Make

this much of my parents

stay alive.

With this beautiful dedication to her parents, Petersen steps onto the ferry with all her literary predecessors: Ophelia, Calypso, voices named and unnamed.

For example, in “Eve Explains The Fall,” we learn from the source that From the start, most things/were horizontal, that What’s called/the Fall from Grace/was more a lateral move, and in fact, that the only mention of falling/came from Adam.

Petersen uses masculine sources as well, such as Rilke and Whitman, but always with open-handed, unflinching feminism. The book is engaging, insightful, sometimes ironic, and always iron-clad.

My Kindred is part love letter, part modern day metamorphosis spun by a poet who earns our trust with the intricate delicacy of antlers and storm. It’s a book with the sensuality of apple flesh and the intricacy of a hornet’s eye. You’ll find yourself on every page.

Previously Published in Blue Mountains Review, Issue 30, September 2023

About the Reviewer

Melody Wilson is a pushcart-nominated poet whose poems appear in Pangyrus, VerseDaily, The Fiddlehead, Crab Creek Review, San Pedro River Review and elsewhere. She is pursuing her MFA at Pacific University. Her chapbook, Spineless: Memoir in Invertebrates came out in 2023. Find more of her work at melodywilson.com.

Special thanks to Carolyn Martin, our Book Reviews Coordinator

Ramadan in Summer by Bruce Parker, reviewed by Melody Wilson

March 15, 2023Finishing Line Press, 2021, 42 pages $14.99

ISBN 978-1646627240

Available at Amazon

Bruce Parker’s Ramadan in Summer transports us to physical and emotional places with spare authenticity. The first example is in the title poem, “Ramadan in Summer,” when the speaker watches a worker listlessly picking things up and putting them down on the fourth floor of an unfinished apartment building visible from his office in the American Embassy in Islamabad. The worker has been fasting while working in the heat, and we empathize when told the heat was not beautiful…the hunger and dread, was not beautiful. But somehow, we envy the experience when we hear ….but the call to prayer was beautiful. This listlessness, wandering through the incomplete building, is an apt metaphor for any life, and picking up and putting down becomes the theme of Section I: from Fasting to Dining.

By third poem in this section, “All Things Will Change,” the poet equates his mind to a leaf losing its grip/on the body’s twig. This image is inverted from the familiar: the tree doesn’t let the twig go, the twig lets go of the tree. In this case, it’s his family who the poet release[s] [his] hold on/those [he] loves.

This sleight of hand shifts us from the first theme, the passage of time, to the second: futility. Parker tips his hand when he titles an elegy to his friend, the poet Jim Harrison, “Oblivion.” He honors the simplicity of Harrison’s passing as a marvelous nothing of no distress/no struggle, no bliss, but ends with It is there before the symphony begins/there after the poem’s last sigh. Then, in “From My Window I See,” we think we are looking at a hummingbird, but actually we are left studying the space the hummingbird leaves behind. We have taken up our lives for examination and find they are just a pause in some larger scheme.

The sensation of interstices is perfected in “The Mind Gathers and Dissolves.” The poet invites us to imagine salt being stirred into a glass of water. Then we’re in the ocean, in the spray of

a whale, particles sprayed into the universe,

gathered up, spit out

swished and rinsed

by the general rule of entropy

its constituents distributed

unformed, forgotten.

In the second half of the book, II: From Wine to Ice Cream, we are no longer discovering our transience, but trying to suspend it. First, we are introduced to the poet’s love in the first poem, “Wine Dream.” Older and dozing, the poet has dreamt her profile and is startled awake. The tone of the book shifts in the last lines of this poem, Before I sleep again/I will hold you/like wine in the cup. The wine, the hummingbird, the vessel of the cup, the emptiness left behind all come to mind.

We are applying the transience we accepted in the first half of the books and are working to suspend it in “Just a Moment, Please.” The lover arrives and the poet is

speechless

in [his] obedience to

some hunger for

what you mean

and how you are here.

Grateful, yes, but the poet is always aware of transience in everything:

one brief moment

in the universe

and time

is like a shower

over us

the good

dripping off

every moment

running away.

Always meticulous, always circumspect, these universal themes are beautifully addressed in the spare poems Parker has included in the collection. There are two long poems, however. In “Poem Beginning with Erasure,” Parker takes us back to the ocean, the waves, and the tide, but this time contracts it to pistil, petal/cup like hips as we experience a moment with his lover. Despite the presence of other people, the lovers spoon, bifurcated/alone as one/plus one. The space between them again reminiscent of the hummingbird: the space of the poem is filled with imagery, but it’s still space, and will eventually still be empty.

In the poem, “Winter is Coming Sure,” late in the collection, the speaker wakes to meditate on the coming of winter, the passage of seasons, the falling of snow, all of which we have considered before in this book.

How shall I greet

the absence of birds

you upstairs asleep

in the middle of the day

knowing

if you go before…

Ramadan in Summer insists we accept life as a mere pause between two states of oblivion. But after the quiet grace with which Parker has broached this news, we face a new, daunting question. Of course, Parker has an answer.

what is certain

is that winter will come

to think it won’t

is to think the leaves of spring

have run away

without waking up.

The unstated admonition is that we live in the present, and the lines are unforgettable.

What a beautiful, thoughtful chapbook this is. Every word matters even as these poems lay bare a futility we try to ignore. Acceptance is the solace, as Parker reminds us in the close of “Winter is Coming Sure”: winter comes/leaves run—/the door’s the thing.

Reviewer Bio:

Melody Wilson’s work appears in Nimrod, Sugar House Review, The Fiddlehead, and on VerseDaily. She received 2022 Pushcart nominations from Redactions, and Red Rock Review, and was finalist for the Naugatuck Narrative Poetry Contest and semi-finalist for the 2022 Pablo Neruda Awards. She is pursuing her MFA at Pacific University. Find her work at melodywilson.com.

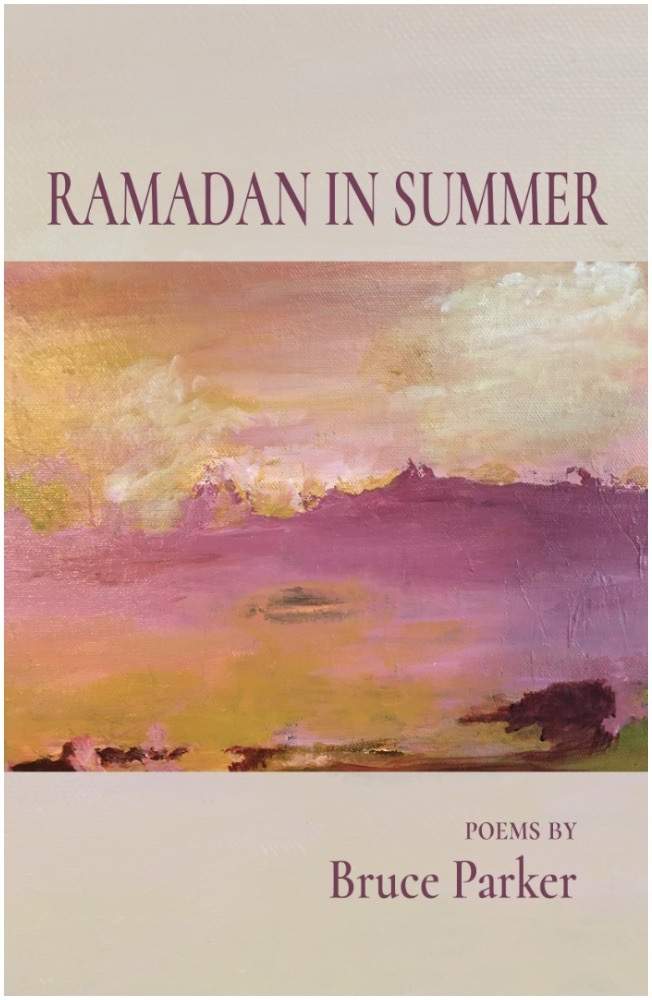

Small Matters Mean the World by David Memmott

February 14, 2023reviewed by George Venn

redbat books, 2022, 73 pages, $16

ISBN 978-1-946970-08-4

Available at www.redbatbooks.com, Ingram, Bookshop.org, Amazon.com, Powells.com

To appreciate David Memmott’s achievement in Small Matters Mean the World (2022), readers might start with the front cover. Memmott’s colorful digital collage suggests a kaleidoscope preparing the reader to celebrate and explore the magic of natural, organic, and psychic forms. Superimposed on that collage, the bold title rises in white cursive script variegated with organic fragments. That combination of title, design, font, statement, and wallpaper assert not only Memmott’s practice as a talented multimedia artist, but also alludes to his lifetime of eclectic practice as poet, editor, publisher, community activist, advocate, and novelist.

Opening and turning the five pages of front matter, readers may be challenged or intrigued by an extended frame: a black-white dazzle of Memmott’s original organic endpaper; interpretive blurbs by editors John Morrison, Peter Grandbois, and David Mehler; a two-page “Contents”; a thematic epigraph from Theodore Roethke; and Memmott’s poem, “Where the Bow Breaks the Wave,” his declaration of resistance to mere realist poetics. These five pages of front matter prepare and frame the twenty-two poems/paintings to follow. Arranged in four distinctive galleries, the poet foreshadows his intention to negotiate relations between realistic and fantastic, microcosms and macrocosm, word and image.

Part I. Titled “Small Matters Mean the World,” Memmott arranges fifteen poems on twenty-three pages, concluding with his thematic title. This is the grandest gallery in the book. There’s variety in form and theme, and unity in length––five of these poems take two pages. In them the poet invites the reader to witness the dramas, the neighborhood nightmares, the waking dreams of urban life in Blue Mountain towns where he has lived for years. He asserts the truth of his title. Microcosm becomes macrocosm, particularities are charged with universals. In both text and sub-text, statement and nuance, the poems engage mortality as they press against the predictable framing of any superficial literalistic narrative.

Part II. Titled “Some Nights My Nothing Rises,” this second gallery is more haunted, the mood more surreal and interior: silence/ moves into my basement (“Some Nights My Nothing Rises”); a last howl clearing the street (“Floodstage”); a mythic bridge fails (“On the Bridge with Gray Owl”); a child’s dreamboat is swamped by writhing unwanted things (“Spilling the Monsters”). A medical nightmare holds the poet down, released only by some far away voice: you were never meant/ to stay here (“Caught in the Updraft”).

In these eight poems, Memmott offers the reader fragments of painful autobiographical memories, then counterpoints them by recalling his own relationship with a wild bird in a fine apostrophe in “To A Flicker in the Attic.”Part III. Titled “Life Is a Beach,” Memmott takes the reader west to another personal and imaginative macrocosm––the Pacific coast ecosystem––where he lived for years. To introduce each microcosm and memory implicit in these five coastal poems, Memmott uses titles and place name signposts as epigraphs or text notes to alert readers to the abundance of characters caught in his macrocosmic saltwater net: fish and crabs, sailors and shipwrecks, molt and messiahs, beaches and tides. To bring the fantastic alive in these oceanic poems, Memmott lands a pair of haunted ghost ship sailors––“The Phantom Sailor Steers for the Stars” and “The Phantom Sailor Washes Up”––deep visions of mythic spacemen and seamen and their washed -up corpses. Part IV. Titled “A Feast Will Follow,” this is the most complex gallery of thirteen poems. The section title is taken from an invitation to a solstice celebration hosted by his fellow poet and friend “[S]agaalgan” whose rural orchard and farm are the site of the gathering. To engage the reader, Memmott provides context, text, chant, and ambience for the longest poem in the collection and one of several in the collection dedicated to women.

Part V. To conclude, Memmott offers a tacit recapitulation: an ending frame of back matter that mirrors the front: a blank page, Wallace Stevens’ epigraph, and a new final poem, “View from the Summit” To complete the circle, the poet once more repeats his organic endpaper and adds limited biographical and bibliographical details. This recursive frame enriches the overall unity and coherence of the book by giving both reader and writer a chance to reiterate and emphasize and contemplate the development of Memmott’s themes. These pages of back matter complete the macrocosm of the book by connecting, as Eliot said, In my end is my beginning. Welcome to David Memmott’s achievement––this magical, lyrical, metaphysical journey.

Reviewer Bio:

Poet, editor, regionalist, and literary historian, George Venn has lived, gardened, written, built, and taught in the Grande Ronde Valley since 1970. Lichen Songs: New and Selected Poems (Kelsay 2017) is his most recent collection. (www.georgevenn.com)The ground at my feet: Sustaining a family and a forest

January 17, 2023by Ann Stinson

Reviewed by Melody Wilson

Oregon State University Press, 2021, 144 pages, $21.95

ISBN-13978-0870711466

Available at Annie Bloom’s and Broadway Books

When I say I love a book, maybe I mean it meets my expectations or it’s better than other books I’ve read. Maybe I mean I learned a lot without working too hard or the topic is important. But I mean it most when the book changes the way I think. All of these are true with Ann Stinson’s memoir, The ground at my feet: Sustaining a family and a forest.

I approached The ground at my feet expecting an apology for tree farming, but I was wrong on two counts. First, this family has nothing to apologize for, and second, I actually don’t know anything about tree farming. Instead, I learned a great deal about this industry from a sensitive, credible source, but I also learned about family dynamics, loss, representation, interdependence, gratitude, resilience, and love. The book is compelling from the beginning as the author and her sister-in-law spread her brother’s ashes through the family’s forest:

I pick a trailing blackberry. It stains my fingertips still coated in Steve’s ashes.

I lick them and make a fingerprint at the top of the first page of my spiral notebook.

I was relieved to see a photo of this image, as well as photos of other descriptions as we follow Stinson through her work teaching in the Bronx and in Oregon, then her decision to resign from teaching to help care for her brother and, ultimately, the farm. I read the book in two sittings and about half-way through the second sitting I began to regret that it was going to end.

The best part of The ground at my feet is its balance. Yes, I learned about forestry and logging, but I also learned a lot about how land in Washington State has changed hands all the way back to the Cowlitz and before, and how timber is marketed in the U.S., in Japan, and in Korea. I learned about workers in mills and on barges, and about the dynamics of a family that include strain and compromise but also enduring love. I gained an understanding of how stewardship actually works and what love of land looks like from the inside, about the importance of compromise and disappointment. But early on, the author quotes Wendell Berry and the lines carried me through the story:

…the world cannot be discovered by a journey of miles, no matter how long,

but only by a spiritual journey, a journey of one inch, very arduous and humbling

and joyful, by which we arrive at the ground at our own feet and learn to be at home.

It’s a broad inch and requires quite the balancing act; the world needs lumber. The land must be tended, which requires long-term management strategy. Strategies change, as do the lives of those involved. Global warming endangers trees, and farmers scramble to keep up. International conglomerates purchase local mills, and entry-level jobs are eliminated even as technology improves. Logs from the same farm wind up as fence boards in Washington, as framework for houses in Japan, for coffins in China, and massive timbers for temples in Korea.

All of this from a single farm in Toledo, Washington, tended by a single family contending with its own leaps of inches—the loss of a son, the aging of the patriarch and matriarch, and passing the land to another generation, all occurring in this century, with its anxieties and responsibilities.

Ann Stinson writes The ground at my feet with genuine humanity and without apology. Her efforts to understand her world, willingness to compromise, and willingness to learn are relentless. For example, on the journey to Korea, she has her first experience of Buddhist prayer in a temple that might well be supported by timbers from her own farm:

press hands together by the heart, bend, kneel, head to the floor, palms up, palms

down, stand. Repeat three times facing the Buddha. I like using my whole body

to pray. There is no question that I am doing something. It moves prayer out

my head and into my body, and the supplication seems to remain as I use my legs

to walk out of the prayer hall.

She is completely present, in this scene and throughout the book, and her presence leaves me with a glimmer of hope that even in industries I wish we didn’t need, there are those who think as I do and who are doing work I can’t imagine. The process is crucial and slow; it takes entire lifetimes to change and evolve. But stewardship is being passed from one generation to the next with the care that comes from understanding the continuity of the forest life-cycle, the lives of wildlife, humans, and trees, all intertwined, all interdependent.

The ground at my feet is so compelling that I resist spoiling the experience by providing too many details, but I was moved again and again––by the family, the depiction of nature, and the effort the author has put into this memoir. But I was most impressed by my own journey—from a limited understanding of the lives lived by those who work on the land to a position of empathy and curiosity. This book is not didactic; Stinson doesn’t set out to appease her reader or even to inform them. She writes her account as a gift…to the land, to [her] family…” to her father, and her brother Steve. That it is also a gift for the reader is unexpected and deeply appreciated. The ground at my feet is a beautiful account and a wonderful, informative read.

Reviewer Bio:

Melody Wilson’s recent work appears in Quartet, Nimrod, and on VerseDaily. New work will appear in Sugar House Review, Minnow, and The Fiddlehead. Reviews have appeared in Colorado Review and on OPA. Her first chapbook, Spineless: Memoir in Invertebrates (2023), was a finalist in the New Women’s Voices competition. Find her work at melodywilson.com.

SMALL FEATHER by Jade Rosina McCutcheon, reviewed by John Van Dreal

December 30, 2022

Finishing Line Press, 2020, 40 pages, $14.99

ISBN: 1646622901

Available at https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/small-feather-by-jade-rosina-mccutcheon/

https://www.amazon.com/Small-Feather-Jade-Rosina-McCutcheon/dp/1646622901

The cover of Jade Rosina McCutcheon’s chapbook immediately caught my eye. Within a kaleidoscope of doodled line and color, a thought bubble speaking for the soul of the work declares, I AM Still Here. Within a few hours, I was at the book’s end, where the last poem “Into Green,” sings:into the stream, out of the dream she answered: ‘here I am’.

SMALL FEATHER begins with a joyous birth of energy in “Australian Bush Solstice” as McCutcheon introduces the grandeur of an evening in her homeland:

Our revelry bounces off full moon light flashes between stampeding clouds as a summer storm excites the air crackling the blue-green gums.

From there, the poet ambles through splendidly descriptive words, doodle drawings, and atmospheric black-and-white photos to the last page, where she concludes in “Into Green”:

A journey ended, yet begun a spider’s web is still being spun, around, within, the frog still sings inside the forest green, there spins.... a dream.

Surrounded by the textures, smells, and tastes of the Governor’s Cup coffee house, McCutcheon and I chatted about her life and work. Her accent and diction are delightful distractions, making almost everything she says both lyrical and engaging. She sees herself as just one person––a small feather in a collective—but also a witness, awake and observing. McCutcheon is academically accomplished, with two doctoral degrees and books on performance and consciousness. SMALL FEATHER is her first chapbook of poetry.

A resident of Australia until she relocated to the U.S. 20 years ago, she spends her days moongazing, writing, drawing, playing music, and engaging in numerous constructive activities, including social work, feminist studies, and supporting survivors of abuse.

Her work is deeply fused to her connections with people, the land, and the cosmos. The Australian terrain and its people spoke to her, spiritually and aesthetically, but when she moved to the States, she lost touch with those sources of inspiration. It took journeys to California’s Mt. Shasta and the Dorland Mountain Arts Community, Salem’s Minto Brown Island Park, and the Oregon coast, combined with her volunteer crisis work, to find the audible frequency of the American experience that now inspires her craft.

In her poem “Turquoise,” she writes:Sun deep carmine falls into dusty orange light sweet cumin smells dance spilling upon all the life in that house coming together deep inside the violet scented turquoise heart.

I may or may not have mentioned to her that those words might be fun to experience with a micro dose of psilocybin, but she certainly did tell me her intention in writing the passage was to create something fabulously imaginative and descriptive.

Her poems range from surreal and dreamy to the metaphysical, then to intensely insightful and boldly, but beautifully, tragic. In “After,” she writes of finding a dead sparrow:I am weeping outside, under the stars as though the bird were you small feather on the hardwood floor a sudden gust and you’re gone.McCutcheon may see herself as a small feather, but her poetic voice is a grand plumage.

John Van Dreal lives in Salem and is a member of the Mid-Valley Poetry Society. He can be reached at [email protected].