BOOK REVIEWS

Snow White, When No One Was Looking by Donna Prinzmetal, reviewed by Carolyn Martin

August 23, 2014Review by Carolyn Martin

“Snow White, When No One Was Looking” by Donna Prinzmetal Snow White, When No One Was Looking

by Donna PrinzmetalCW Books, Cincinnati, OH, 2014

ISBN: 978-1625490841

2014, 84 pages, $16.20Reading Donna Prinzmetal’s collection of persona poems, Snow White, When No One Was Looking (Cincinnati, OH: CW Books, 2014) is like falling down a rabbit hole and landing in the midst of a Salvador Dali painting. While her fairytale heroine has been part of our collective consciousness for generations – from the Grimm brothers to Walt Disney to ABC’s Once Upon a Time – no one has ever met a Snow White quite like the one Prinzmetal creates. The poet invites us into the surreal inner world of this iconic heroine with language and images that are fresh and astonishing. In the process, she ensures that we will never look at this fairytale the same way again.

First of all, the foundation of this collection is built upon the original Grimms’ fairytale. The three sections dividing the poems – white as snow, red as a blood, black as ebony – reference the qualities Snow White’s birth mother wished for in a daughter. She got her wish but died in childbirth, thus setting the stage for the appearance of the evil stepmother, the compassionate huntsman, the protective dwarves, and, of course, the Prince.

But that traditional foundation begins to crack from the very first poem when Snow White announces, “I gotta tell you folks, I’ve been around the forest a time or two. Hold onto your flying sombrero because my America, the black forest, isn’t what you expect” (“Everyone Loves a Happy Ending: Snow White Has Her Own Show”).

From that moment on, we hear a voice we’ve never heard before; and every plot line, theme, and character we thought we knew in the fairytale is blown to smithereens. As Snow White proclaims in “Snow White Sets the Record Straight”:

It didn’t happen like everyone believed, in black

and white, dwarves in the cottage, a tsunami loose

in my body, then

unquenchable silence into my clear coffin sleep

while you were brooding over me ….

I never meant to start my own rumor.Undoing that “rumor” is the driving force behind each poem and Snow White is securely enthroned in the driver’s seat.

For example, Prinzmetal’s Snow White is a time traveler. She doesn’t merely reside in the fairytale world of magic mirrors, poison apples, dwarves and crystal coffins but hops to contemporary settings. In one poem she sits in front of a TV watching Oprah and Jerry Springer (“Snow White Watches Daytime TV”); in another she admits, “I’m never on time./I forget my century” (“Snow White Sets the Record Straight”). That statement becomes clearer when we stumble upon her references to Joan of Arc, Debussy, Chopin, Kafka, Errol Flynn, Dali, Charlton Heston, Marilyn Monroe and Madonna.

This Snow White is a handful for any prince – charming or not – who would attempt to love her. In “Snow White: Taxidermy,” one of several love-themed poems, she says:

Let me confess

the ecstasy was temporary

as a tulip’s bloom.

You would be mortified to know

how often I pretended to love you

in that mango colored tuxedo

you called woe.And this Snow White is a character both disturbed and disturbing. She wants “so desperately to speak the language/ of the insane without being insane … (“Snow White Meets Salvador Dali”). She claims, “I am your worst/nightmare” (“Snow White: Ventriloquism”). She wishes to “devour the raw and uncleansed flesh of everyone who has ever betrayed me” (“If I Could Sew: Snow White”).

While reading this collection, I kept asking myself, “What kind of poetic sensibility could have imagined and imaged this vision of this character?” Indeed, the depth and reach of Prinzmetal’s poetic imagination is nothing short of a revelation. Like Snow White, she could tell us, “I am tired of telling the same story” (“Snow White Revises Her Fairy Tale”), yet we feel she never tires of creating surreal landscapes filled with different versions of the same story that haunt and delight, horrify and mystify.

If one of the purposes of poetry is to make us slow down and see the world with new eyes, then Snow White, When No One Was Looking fulfills that purpose. After savoring this collection, we can only admit to ourselves – and to each other – we weren’t really looking after all. Now we are.

Reviewer Bio: Carolyn Martin is blissfully retired in Clackamas, OR, where she gardens, writes, and plays with communities of creative colleagues. Currently, she is president of the board of VoiceCatcher, a nonprofit that connects, inspires, and empowers women writers and artists in greater Portland, OR, and Vancouver, WA.

Woodstock Baby, by Joan Dobbie, reviewed by Tim Volem

July 23, 2014The Unforgettables Press

([email protected])

ISBN 978-1-4923138-3-0

2013, $9.00Joan Dobbie’s Woodstock Baby is described on its cover as a Novel in Poetry, and while it is not technically a verse novel, with a formal structure (stanzas, rhyme scheme), it is composed of short free verse poems that tell a story.

The story is set in Boston in the late 60s/early 70s and documents the lives of a network of friends who are immersed in the counterculture of that time. It is an insular community, focused on the art of living, more than on making a living, and its characters are artists and dropouts, students and cab drivers, Viet Nam vets and young parents, particularly young mothers. As Joan Dobbie says in her Introduction, addressed to friends, her work is fiction and “like most fiction, it is based upon life.” In the work, Joan is named Ruth who marries a young man named Ryan and they soon have a daughter named Jenny Fay. In an Afterword, Dobbie lists the cast of characters whom we’ve come to know from reading the short poems. The list describes the characters’ roots, which display a range of cultures and class. But what connects the characters is their youthfulness and the lure of Boston (most of them are from someplace else). There is a compelling sense that the immediate is open to great possibility.

A central theme in Woodstock Baby is pregnancy and its attendant developments- childbirth and childrearing. The poem that is reprinted on the book’s back cover, with the following two-line title, captures the focus of much of the story:

Don’t let anybody tell you different

PREGNANCY IS CATCHINGAll summer I stayed with Mitch

& Marlene

who was pregnant.All summer I studied

the Pink Pregnant book, rested

my hand on her belly,

breathed

the salt spice of that baby.That was the summer before

the summer my baby was born.Dobbie’s poems are mostly short and use white space liberally, making for ease of reading. Often there is a central image that captures a scrap of time and easily conveys character, like the poem “Onion Soup,” presented early in the story:

ONION SOUP

Joby will never be poor

hatesShe will be a rich

& charismatic writer& so

cooks onion soup

which she says is the soup

of the wealthy& grand.

We top it with croutons & sharp

cheddar cheese.We hold our spoons

with pinkiesSometimes a wry humor is presented in the snapshots of life in Boston, as in the following, one of the longer poems in the novel:

BEWARE OF MARRYING A PAINTER

If your new husband

is an artist

& you’re just beginning

to show

& you’re still

very young

& tight

& prettythen you may

end up spending a lot

of long shivering hoursstanding absolutely stark naked

(absolutely

no moving)in the middle of the frigid

landlord-green

living room(which is your only room)

probably by the mantel

(& the fireplace boarded up)probably with your right arm

raised

like Miss Liberty& your left

on your hip & your backarched seductively.

In addition to Ryan and Ruth’s friends and housemates, there are appearances made by her parents and her brother and sister, too. An inclusiveness prevails in the apparent casual living being experienced by Ruth in Boston. The poem “Jenny Talking to Grandma” is one such appearance of immediate family:

JENNY TALKING TO GRANDMA

on the phone,

she pressesthe heavy black

receiverto her ear,

swingingher right leg

back & forthback & forth

like little girls do

& her eyesare the river

at night.As the novel proceeds, there are challenges presented to many of the characters we’ve come to know, and Ruth of course is no exception. In small increments, we come to learn much about many of the inhabitants of the rundown house in Boston.

What seems like a casual collection of impressions does develop into the fabric of a story and builds to an ending that leaves Ruth in control but on the verge of a future that is filled with unknowns. Woodstock Baby documents a version of the 60s zeitgeist in a seemingly casual manner but the effect of all the short poems is one that stays with the reader. And upon completion, this reader found himself visiting the story again and gathering a greater sense of the characters as they engage in concerns of their youthful lives.

Copies of Woodstock Baby may be ordered directly from Joan Dobbie ([email protected]). The book is also available online through Amazon.

Reviewer Bio: Tim Volem is a member of the Lane Literary Guild in Eugene and has published poems in The English Journal, Tiger’s Eye, and Carapace.

The Parachute Jump Effect by Judith Arcana, reviewed by Penelope Scambly Schott

June 26, 2014Review by Penelope Scambly Schott

The Parachute Jump Effect

by Judith ArcanaUttered Chaos Press (www.utteredchaos.org)

ISBN 978-0-9823716-9-5

2012, $10.00Unless you are of a certain age and grew up in Chicago, you won’t understand the title of this chapbook until you get to the final poem, a shared recollection of a long-gone ride in a vanished amusement park.

Riverview’s gone.

It’s been disappeared. This is all about history –

that’s where the parachute jump is now.The ride was about choosing to rise in order to fall – the poet felt the fall in her heart, the woman she is addressing felt the fall in her throat. This was the thrill of anxiety.

Throughout Judith Arcana’s chapbook, we hear the voice of a wryly urban poet playing with questions and anxiety. The book opens with two scary dream poems leading to a poem which dissects uncertainty.

Ok, All Right, Yes

You think you know what’s going to happen

but you don’t, you know only what you think

is going to happen –After examples of expectations that may or may not come true, the poem concludes:

you think you’ll live until you die

and hey – ok, all right, yes

you can have that one

that one’s got to come true.Much of the pleasure of these poems lies in their tone, serious but often witty. Even when Arcana becomes dark and philosophical, as in “Lois, Questions” where she addresses the dead friend to whom she has dedicated the book, she is also playing with ideas. Here are some of her questions:

What’s it like out where you are?

Is there music? Is there eating? Sleeping?

Can you fly? Can you see me? Are you coming back?

Will you be someone else? A wolverine, or a stalk of corn?

Do you still have cancer when you’re dead?

Or does it go away after it kills you? Are you angry?In this collection Arcana is not angry but she is chronically perplexed – and never in an abstract way. Whether she writes about safety matches or bakeries, she is exploring and reporting back on the mind at work. You will want to follow her journey.

Reviewer Bio: Penelope Scambly Schott’s verse biography A Is for Anne: Mistress Hutchinson Disturbs the Commonwealth received an Oregon Book Award. Recent books are Lovesong for Dufur and Lillie Was a Goddess, Lillie Was a Whore. Forthcoming Fall 2014 is How I Became an Historian. Penelope teaches an annual workshop in Dufur, Oregon.

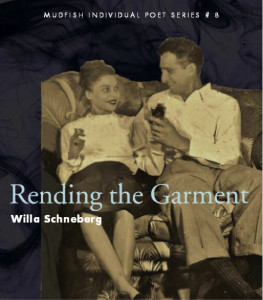

Rending the Garment by Willa Schneberg, reviewed by Eleanor Berry

May 22, 2014Review by Eleanor Berry

Rending the Garment

by Willa SchnebergBox Turtle Press

ISBN 978-1-893654-14-3

2014, 103 pp., $16The couple in the cover photograph compel our gaze. “Should I recognize them?” we may wonder, thinking they must be stars in a classic film of the 1940s. As we read, we discover that they made much the same impression on their contemporaries:

At family affairs distant relatives

asked if they were on the stage,

and my parents flattered and tired

would shake their heads, no,

as they left the floor to look for their table.Superimposed on the cover photograph of the vivacious young woman and debonair young man, clearly entranced by each other as they clink their glasses in a toast, is the book’s title, Rending the Garment. That is what this book does. The poems in various voices and the documents in various hands that compose it are like so many scraps of clothes torn in mourning. Together, they tell a family story with an adequate complexity that no narrative from a single point of view could convey.

The characters are Ben, Esther, and Willa—the New York Jewish parents and the poet, their only child. The book’s three-part structure—“Ben, Esther & Willa,” “Esther & Willa,” “Willa”—tells, in the starkest terms, how time has dealt with them.

Reading this book, I learn to know Ben, Esther, and Willa in somewhat the way I learn to know people in the actual world. I piece together a sense of their characters and a story of their lives from fragmentary encounters. But the book differs from the world in that it reveals the episodes of their lives chronologically: much more than is typical for a collection of short poems, this one induces readers to read it in order. In the book, again unlike the world, the speakers change unpredictably, and it isn’t always immediately evident who is speaking in a given poem. I found that the shifts kept me alert and attentive.

Before reading this book, I had already met Esther—in The Books of Esther, Willa’s 2012 exhibit at the Oregon Jewish Museum, which powerfully documented and memorialized her mother’s life, especially through her writings in a succession of notebooks when surgery for throat cancer had “cut out her voice,” and in a small, exquisite collection of associated poems from Paper Crane Press. I remembered how, without voice, she had made writing her way of speaking, her “words—wise, fierce, raucous / filling up the pages of the world.” I remembered her in an airplane restroom, literally deaf to the impatient knocks and shouts of fellow passengers, efficiently grinding her pills and pouring the powder, along with her liquid nutrition, into her jejunostomy port.

Through Rending the Garment, I learn more of Esther before and during her marriage to Ben. I meet her as an 11-year-old winner of an essay contest on fire prevention, who knew that she couldn’t write about boys “lighting matches underneath swing sets.” I meet her as a young mother, half-heartedly playing mahjong with other young Jewish mothers, not revealing “that I have a B.A. and / don’t care about mastering this game.” I meet her as a striking teacher, cringing to hear “some fellow strikers / call scabs ‘nigger lovers.’” I meet her in the hospital while her husband is dying in another part of the same hospital, and at his funeral, where, she can’t hear her daughter who is speaking for her.

Besides learning more of Esther, I meet Ben and am drawn into his struggles to be the person that he imagines himself, the person that Esther and Willa, for a time, believe him to be. Loveless conception, trauma of work in a civil service job patrolling in the Holland Tunnel, frustration and failure as a teacher, humiliation of working as a waiter, hospitalization for depression, struggle to overcome tunnel phobia, betrayal by age: all these circumstances and experiences of a difficult and particular life make the man with the matinee-idol looks in the cover photograph a fellow human for whom I feel both exasperation and empathy. They are conveyed mostly through persona poems in Ben’s voice.

For me, the most heartbreaking of the poems in Ben’s voice is “Long Day’s Journey into Night at the Seaview Branch of the Brooklyn Public Library,” where he speaks of playing James Tyrone, Sr., “failed Shakespearean actor, / who went for the bucks rather than greatness,” in Eugene O’Neill’s tragic masterpiece portraying his own parents and the family from which he emerged. “Holding the script in [his] hand,” Ben imagines himself “not here in the conference room / of a backwater branch of the library,” but “at the Helen Hayes electrifying the audience.”

Even without that poem, I would have thought of Long Day’s Journey into Night and of O’Neill’s dedication of that play to his wife in gratitude for her love, which enabled him to “face my dead at last and write this play—write it with deep pity and understanding and forgiveness.” Willa, likewise, has faced her dead, and written of them with deep empathy. What she has done in Rending the Garment reminds me also of the final lines of Robert Lowell’s book-length sequence Day by Day:

We are poor passing facts,

warned by that to give

each figure in the photograph

his living name.She has given the woman and man in the photograph on the book’s front cover their living names—and voices.

On the back cover of the book there is another, smaller photograph—of a small girl seen from behind as she walks away, holding a book. This is apparently the young Willa. The way she appears on the cover reflects the supporting role she plays in a book dominated by the figures of her parents. The final section, “Willa,” functions as a sort of coda after the climax of the title poem. Its most poignant poem, “Willa’s Hairs,” seems to be spoken in the voice of her husband, Robin: “I wonder… after she is gone, / could my green-eyed one be made again / from a single long white hair.”

Some books of poetry leave memories of particular images or specific lines; others leave impressions of a certain emotional tone. Rending the Garment leaves me with the remarkable individuals to which it has given voice.

Reviewer Bio: Eleanor Berry moved to the Salem area from Wisconsin in 1994. A former teacher of writing and literature at Willamette University, Marquette University, and other colleges, she is a past president of the Oregon Poetry Association, and serves on the boards of the Marion Cultural Development Corporation and the National Federation of State Poetry Societies. Her poetry and essays on poetry have been widely published in journals and anthologies. Her book Green November (Traprock Books, 2007) is a collection of poems derived from her acclimation to western Oregon.

Controlled Hallucinations by John Sibley Williams, reviewed by Penelope Scambly Schott

March 27, 2014Review by Penelope Scambly Schott

Controlled Hallucinations

by John Sibley WilliamsFutureCycle Press

ISBN 978 – 1938853227

2013, 78 pp., $14.00

http://johnsibleywilliams.wordpress.com

This book is well-titled. It contains the poetry of allusion. Williams’ go-to symbols are such elements as the sea, mirrors, birds, or even gravity itself. These appear frequently in this poetry of transparent mystery.

This book is well-titled. It contains the poetry of allusion. Williams’ go-to symbols are such elements as the sea, mirrors, birds, or even gravity itself. These appear frequently in this poetry of transparent mystery.What is there is almost there. I don’t mean that the poems are vague – though they are short on specifics – if there is a tree we don’t know what kind of tree, if there is a bird, it is rarely named – but the poems create a hallucinatory aura of magic where everything stands for more than itself. Perhaps this is the quality that John Sibley Williams and Anatoly Molotov are embracing in the new journal The Inflectionist Review.

The poems themselves are numbered rather than titled, thus coming at us like dreams without giving us any prompt or shove as to how to read or interpret. We do not gloss so much as experience. The magic of this world is not hidden but lurks near the surface.

Williams is obsessed with language. Several poems in this volume might serve as an ars poetica. In poem XXI he says that even as a child when a storm was approaching and others did practical things,

I would cry out a list of synonyms

for what was to come:tempest blizzard gale squall cloudburst

chaos

upheavalHe would survive via words and he can still “take comfort in their distance.”

Here in its entirety is one of my favorite poems about his explorations of language:

XLVIII

Forks and knives dull,

teeth worn down,

I am left to eat

in broken English.I try to step around the flavors

passed through so many mouths,

around the stacks

of overused plates

that have cracked with wear–

the only plates at the table.

I try to trace each cliche back

to a curious hand

tapping a white cane

in hopes of rediscovering

my blindness.How better to describe a search for the original freshness of English?

Williams’ approach to defining the undefinable works especially well in his poems about love, that front-runner in indescribable human experiences. He asks, in poem IX,

When does it end,

this search for a more intimate gravity,

this need to replicate embrace?Perhaps XLII offers a semi-answer: “Most of me/attended/the Big Bang/just to ask it/if other theories/were possible.” The speaker stomps around the cosmos waiting for an answer which he then can’t hear because “I’d left/my ears/far below/on your/sleeping chest.”

Controlled Hallucinations is one of those unusual books that teaches you how to read it. Once I could let go and be taken up in the hallucinatory process, I learned to enjoy where it took me. You might too.

Reviewer Bio: Penelope Scambly Schott’s most recent books are LOVESONG FOR DUFUR and LILLIE WAS A GODDESS, LILLIE WAS A WHORE. Her verse biography A IS FOR ANNE: MISTRESS HUTCHINSON DISTURBS THE COMMONWEALTH received an Oregon Book Award. She teaches an annual workshop in Dufur, Oregon.