Review by Eleanor Berry

Rending the Garment

by Willa Schneberg

Box Turtle Press

ISBN 978-1-893654-14-3

2014, 103 pp., $16

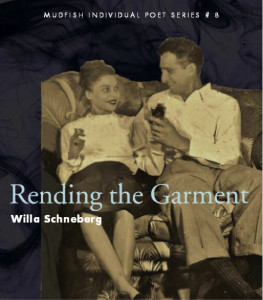

The couple in the cover photograph compel our gaze. “Should I recognize them?” we may wonder, thinking they must be stars in a classic film of the 1940s. As we read, we discover that they made much the same impression on their contemporaries:

At family affairs distant relatives

asked if they were on the stage,

and my parents flattered and tired

would shake their heads, no,

as they left the floor to look for their table.

Superimposed on the cover photograph of the vivacious young woman and debonair young man, clearly entranced by each other as they clink their glasses in a toast, is the book’s title, Rending the Garment. That is what this book does. The poems in various voices and the documents in various hands that compose it are like so many scraps of clothes torn in mourning. Together, they tell a family story with an adequate complexity that no narrative from a single point of view could convey.

The characters are Ben, Esther, and Willa—the New York Jewish parents and the poet, their only child. The book’s three-part structure—“Ben, Esther & Willa,” “Esther & Willa,” “Willa”—tells, in the starkest terms, how time has dealt with them.

Reading this book, I learn to know Ben, Esther, and Willa in somewhat the way I learn to know people in the actual world. I piece together a sense of their characters and a story of their lives from fragmentary encounters. But the book differs from the world in that it reveals the episodes of their lives chronologically: much more than is typical for a collection of short poems, this one induces readers to read it in order. In the book, again unlike the world, the speakers change unpredictably, and it isn’t always immediately evident who is speaking in a given poem. I found that the shifts kept me alert and attentive.

Before reading this book, I had already met Esther—in The Books of Esther, Willa’s 2012 exhibit at the Oregon Jewish Museum, which powerfully documented and memorialized her mother’s life, especially through her writings in a succession of notebooks when surgery for throat cancer had “cut out her voice,” and in a small, exquisite collection of associated poems from Paper Crane Press. I remembered how, without voice, she had made writing her way of speaking, her “words—wise, fierce, raucous / filling up the pages of the world.” I remembered her in an airplane restroom, literally deaf to the impatient knocks and shouts of fellow passengers, efficiently grinding her pills and pouring the powder, along with her liquid nutrition, into her jejunostomy port.

Through Rending the Garment, I learn more of Esther before and during her marriage to Ben. I meet her as an 11-year-old winner of an essay contest on fire prevention, who knew that she couldn’t write about boys “lighting matches underneath swing sets.” I meet her as a young mother, half-heartedly playing mahjong with other young Jewish mothers, not revealing “that I have a B.A. and / don’t care about mastering this game.” I meet her as a striking teacher, cringing to hear “some fellow strikers / call scabs ‘nigger lovers.’” I meet her in the hospital while her husband is dying in another part of the same hospital, and at his funeral, where, she can’t hear her daughter who is speaking for her.

Besides learning more of Esther, I meet Ben and am drawn into his struggles to be the person that he imagines himself, the person that Esther and Willa, for a time, believe him to be. Loveless conception, trauma of work in a civil service job patrolling in the Holland Tunnel, frustration and failure as a teacher, humiliation of working as a waiter, hospitalization for depression, struggle to overcome tunnel phobia, betrayal by age: all these circumstances and experiences of a difficult and particular life make the man with the matinee-idol looks in the cover photograph a fellow human for whom I feel both exasperation and empathy. They are conveyed mostly through persona poems in Ben’s voice.

For me, the most heartbreaking of the poems in Ben’s voice is “Long Day’s Journey into Night at the Seaview Branch of the Brooklyn Public Library,” where he speaks of playing James Tyrone, Sr., “failed Shakespearean actor, / who went for the bucks rather than greatness,” in Eugene O’Neill’s tragic masterpiece portraying his own parents and the family from which he emerged. “Holding the script in [his] hand,” Ben imagines himself “not here in the conference room / of a backwater branch of the library,” but “at the Helen Hayes electrifying the audience.”

Even without that poem, I would have thought of Long Day’s Journey into Night and of O’Neill’s dedication of that play to his wife in gratitude for her love, which enabled him to “face my dead at last and write this play—write it with deep pity and understanding and forgiveness.” Willa, likewise, has faced her dead, and written of them with deep empathy. What she has done in Rending the Garment reminds me also of the final lines of Robert Lowell’s book-length sequence Day by Day:

We are poor passing facts,

warned by that to give

each figure in the photograph

his living name.

She has given the woman and man in the photograph on the book’s front cover their living names—and voices.

On the back cover of the book there is another, smaller photograph—of a small girl seen from behind as she walks away, holding a book. This is apparently the young Willa. The way she appears on the cover reflects the supporting role she plays in a book dominated by the figures of her parents. The final section, “Willa,” functions as a sort of coda after the climax of the title poem. Its most poignant poem, “Willa’s Hairs,” seems to be spoken in the voice of her husband, Robin: “I wonder… after she is gone, / could my green-eyed one be made again / from a single long white hair.”

Some books of poetry leave memories of particular images or specific lines; others leave impressions of a certain emotional tone. Rending the Garment leaves me with the remarkable individuals to which it has given voice.

Reviewer Bio: Eleanor Berry moved to the Salem area from Wisconsin in 1994. A former teacher of writing and literature at Willamette University, Marquette University, and other colleges, she is a past president of the Oregon Poetry Association, and serves on the boards of the Marion Cultural Development Corporation and the National Federation of State Poetry Societies. Her poetry and essays on poetry have been widely published in journals and anthologies. Her book Green November (Traprock Books, 2007) is a collection of poems derived from her acclimation to western Oregon.