BOOK REVIEWS

Every Door Recklessly Ajar by Nancy Flynn, reviewed by Ann Staley

March 7, 2016Reviewed by Ann Staley

Every Door Recklessly Ajar

By Nancy Flynn

Cayuga Lake Books, Ithaca, New York

ISBN 9781681110356

2015, 72 pp., $12 (on Amazon)

Nancy Flynn.com Nancy Flynn’s slender volume of poems is filled with joy and mystery, grief and remembrance. It is the home of many pleasures, beginning with the zany, And I Will Tell You A Story, about how a tree grew out of a piano. Each of the four sections begins with a lovely quote like this one by Larry Levis:

Nancy Flynn’s slender volume of poems is filled with joy and mystery, grief and remembrance. It is the home of many pleasures, beginning with the zany, And I Will Tell You A Story, about how a tree grew out of a piano. Each of the four sections begins with a lovely quote like this one by Larry Levis:And so you put your hand out,

Palm open,

And then you feel, or you begin to feelThe opening poem, Code Talker, is surely meant to be a word puzzle, Say lipstick and mean ghost stripes on the prow, say this and mean that. It is playful with some serious undertones: Say liver and mean none who survive. Do poets always write in code, I wonder. And I think, Yes. Yes we do, for we are translators of moments.

When I read the next poem, Runaway, I immediately wrote my own poem. You might feel the same invitational pull. Prepositions by Nancy Flynn; responses from this reviewer:

from Green Acres

from a 50’s red brick ranch-house

from a pair of mis-matched parents

to living in the Pacific NorthwestThe Winter We Lived In The Church & It Snowed Daily & The First Barrel Of Crude Oil Traveled Successfully Through The Trans-Alaska Pipeline is worth reading even after the title!

At the center of the collection, an eight page poem, Tupelo, A Gospel According To, begins with, The day Elvis died, The Tupelo-Gainsville tornado outbreak, of April 1936 when 233 people died, 700 hurt, but they didn’t count/any body/black and, I can remember/clarity, could see through the drip, my life clipped/ swervy yet two-lane. And don’t you want to write your own?

Harrisburg, A Gospel According To

In late-winter, crocus & daffodils.

in spring, apple blossoms,

in summer, green grass,

in autumn, bare branches

In July, Hurricane Hazel,

moves inland to Central Pennsylvania.

Lightening and thunder,

torrential rain soaks your clothing

as you run to the safety of the front porch.You see how every moment in the present

connects you directly to the past?It’s why we write.

Section 3 begins with the poem, How To Weather A Day Of 24-7 Media-Drenched Weather Hysteria which contains the book’s title. All I remember is the day of September 11, 2001. Waking to the radio report of a second plane hitting the World Trade Center. Watching people leap from fiery top floor windows. If you were alive then, you remember exact moments from that day—hearing and seeing the news. Because I live on the west coast, it felt as unreal as watching a movie, played over and over again for twelve hours. I joined my friend, stay-at-home mother of two, and we watched together in her living room. I don’t remember eating or drinking anything but coffee. Caffeine lifts the tarnish off silverware and assists your “coming to grips” with the new reality: Terrorism.

A page or two later, I encountered the poem, Transubstantiation. I recognized the word, but wasn’t sure of its meaning, so I looked it up in my Dictionary of the English Language, page 1507. I’m going to let you look this up yourself.

The final section contains the poem with the longest title: Complicity, Or Poem Written After Days Sitting Out On Our Explorer Of The Seas Stateroom Balcony & Staring Into That Sea Traversed For Hundreds Of Years By Ships Of The Middle Passage. Why does the poet use such a long title? Marge Piercy told me to make my titles exact and irresistible. After Complicity the rest of the title does jus that.

This poem is followed by a sonnet, a villanelle, and Cape Disappointment, which concerns itself with a very cold weekend in the 1955 Spartan Manor, at the Sou’wester Lodge & Vintage Travel Trailer Resort in Seaview, WA.

I have visited Seaview twice in my life and both times it was blustery, cold and gray. There’s a lighthouse, and a US Naval base, still occupied. You can see platoons of soldiers marching, raising the flags, young men who look handsome in their “whites” or their “blues.”

The volume closes with a prose poem, Mercator Projections,

This is the map where I live now. Pipedream

memory, land.Reviewer bio: Ann Staley’s third collection of poems, Afternoon Sky Harney Desert, will be published in April, 2016.

Reverberations from Fukushima: 50 Japanese Poets Speak Out, reviewed by Ruthy Kanagy

January 9, 2015Review by Ruthy Kanagy

Reverberations from Fukushima: 50 Japanese Poets Speak Out

Edited by Leah Stenson and Asao Sarukawa Aroldi

Inkwater Press (Portland, Oregon)

ISBN: 9781629010656

2014, 192pp., $14.95 3.11.11 is a date forever imprinted on the memories of Japanese and other persons who were in Japan on that fateful day. A massive tsunami launched by a ‘thousand-year’ magnitude 9.0 earthquake inundated 400 miles of Pacific coastline north of Tokyo – about the distance from San Francisco to Los Angeles. It took the lives of 18,000 people and swept away farms, homes, fishing villages and whole cities. In the days following, multiple hydrogen explosions and meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi (No. 1) Nuclear Power Station, 160 miles north of Tokyo, forced the evacuation of 140,000 citizens who had to abandon pets, livestock, farms, and businesses, tearing apart centuries-old ways of life.

3.11.11 is a date forever imprinted on the memories of Japanese and other persons who were in Japan on that fateful day. A massive tsunami launched by a ‘thousand-year’ magnitude 9.0 earthquake inundated 400 miles of Pacific coastline north of Tokyo – about the distance from San Francisco to Los Angeles. It took the lives of 18,000 people and swept away farms, homes, fishing villages and whole cities. In the days following, multiple hydrogen explosions and meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi (No. 1) Nuclear Power Station, 160 miles north of Tokyo, forced the evacuation of 140,000 citizens who had to abandon pets, livestock, farms, and businesses, tearing apart centuries-old ways of life.Almost four years later, we in the U.S. hear little about the aftermath of the nuclear accident and on-going policies of government agencies and Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) — who built the plant in rural Fukushima to supply power to Tokyo — in dealing with the contaminated land, sea, air and the daily lives of the ‘nuclear refugees’ who cannot return home.

This unusual collection of poems fills a gap in our understanding of the human impact of nuclear power on the people of Fukushima prefecture, on Japanese society, and on all humanity. Here is a rare chance to hear fifty Japanese poets speak to us directly in strong, clear voices, unfiltered by media or government. Originally composed in Japanese, skilled translators have made the poems accessible to English readers.

The fifty poems originally appeared in a larger Japanese-English edition entitled, Farewell to Nuclear, Welcome to Renewable Energy: A Collection of Poems by 218 Poets, edited by Hisao Suzuki, Jotaro Wakamatsu, et. al. (Tokyo: Coal Sack Publishing Company, 2012).

The volume opens with a preface by editor Leah Stenson followed by several essays and commentary by Suzuki, Wakamatsu, and others, that inform and give historical context to the poems. Following are excerpts from eight poems in the anthology, which address a range of themes from fear, betrayal, contamination, nature’s bounty, and love of ones home, to the politics of secrecy and the human significance of technological failure.

In “A Phantom Country of Civilization – From Hiroshima to Fukushima,” Ryu Nishida reveals the repeated mistakes of the country’s leaders and people, who followed in the dark.

A Phantom Country of Civilization – From Hiroshima to Fukushima

Swallowed up in a muddy stream,

though aware of the foolishness of the country’s policies,

the people of the country chose, without logic, the way of darkness.

They knew no way other than fighting with bamboo spears

against heavily-equipped invading forces. . . . . . . . . . .

Didn’t this country come trudging along,

carrying the darkness of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on its back?

A myth about the safety of nuclear power plants had been constructed

and nuclear power plants now jostle each other for space on this island

country.. . . . . . . . . . .

The last stanza is full of powerful imagery regarding the current situation.

We stand, powerless and bare-skinned,

in the scorching sunlight.

While radioactivity dances wildly in the wind and light,

no one can see it, or has any way to deal with it.

we stand, motionless, in the flow of time that passes from life to death.Note: From 1962, Japan built 54 nuclear power plants that supplied a third of the country’s energy needs. All were shut down after the meltdowns at the Fukushima plant. There is fierce political, scientific, and social debate over whether and when to restart them. The government announced intentions to restart the first one, the Sendai nuclear power plant in Kyushu, in early 2015.

Masami Tanizaki, in “Transition of a Myth,” expands the nuclear dialog to the global stage, charging that by ignoring the effects of radiation we have endangered children everywhere. We have to dig deep under the rubble and “discern the words” of “the ripe fruit hanging on the branches.”

Transition of a Myth

Both those who know about Chernobyl

and those who don’t know about Chernobyl

are surely now aware of the keen sensitivity

of the tender organs and bones inside of

babies and infants, boys and girls…. . . . . . . . . . .

We already knew of

the wretched spectacle of nuclear testing in the Pacific,

the madness at Semipalatinsk

and the Iraqi children hit by depleted uranium rounds.. . . . . . . . . . .

Will it turn out to be a myth

that they can return to the place where they were born?We must keep looking at even what is hidden in the rubble,

We have to discern the words from the silence

of the ripe fruit hanging on the branches.The posture of gaman, or patiently enduring adversity, is a strong culture value in Japan, particularly in rural, traditional communities of the Tohoku (northeast) region, which includes Fukushima prefecture. In “Give Us Back Everything,” Yasunori Akiyama tell us that, “Those driven from their homes by radioactivity” are being treated “as an unimportant minority.” It is time to “locate the source of the pain” and “cry out loudly” to those in positions of power.

Give Us Back Everything

In an abandoned hamlet

several dozen cows

tied to cowsheds died, sprawled on the floor,

leaving tooth-marks on the wooden door frames.

From their parched hide,

from their hooves kicking the air

from the rusty iron beams of the cowshed

from the dirt of the floor,

from the dent in the roof,

from the roots of the grass, trunks of trees, and the air,

something is silently watching.. . . . . . . . . . .

We must not be patient.

To be patient is to run away.

To endure is to look away from reality.

When it hurts, we should cry out loudly…. . . . . . . . . . .

The last stanza is a chorus which “We should say in unison/ to those who hid what they didn’t want us to see”:

Give us back our cows! Give us back the fodder!

Give us back our homes, farms, grass and trees!

Give us back our water, air, insects, fish and birds!

Give us back our neighbors!

Give us back peace for the babies not yet born!

Give us back everything that once was!

Give us back the future that is yet to come!Akiyama’s last two stanzas bring to mind a poem by Sankichi Toge, who endured the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. His “Give Back the Human,” written in 1951, is engraved on a monument in Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park:

Give back my father, give back my mother;

Give grandpa back, grandma back;

Give me my sons and daughters back.

Give me back myself.

Give back the human race.

As long as this life lasts, this life,

Give back peace

That will never end.When Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) built the nuclear power plants in Fukushima’s verdant, coastal area to supply energy to metropolitan Tokyo 160 miles away, they convinced many, though not all, local citizens of the economic benefits — construction jobs and employment — using slogans such as, “Clean, Safe Nuclear Power.”

As a young woman just out of school, Hatsuko Hara was happy to get a job with TEPCO. Her mother warned her, however, that “The things that people do are not perfect./ A nuclear plant is the same as an atomic bomb.” In her poem she informs the reader of why she terminated her job five months after the nuclear accident. Her message is one of sorrow, betrayal, and a new resolve.

The Day My Professional Career Ended

On August 31, 2011,

my professional career ended.

I retired from my company.. . . . . . . . . . .

When I entered the company I told my parents,

Father and Mother,

Don’t participate in the anti-nuclear movement.

I am a member of Tokyo Electric Power Company.. . . . . . . . . . .

I felt proud to be working for a company that produces electricity.

I found my partner

and bore two children.. . . . . . . . . . .

Now, I am

a citizen concerned with conserving electricity

so that we can live without nuclear power.In “Swindling of One Million Years,” Keiichiro Fujitani accuses “Those who transplanted the genes of the sun to this planet!/ Those who shoot arrows to the sun from this tower of Babel!” of ignoring the long-term consequences of the use of nuclear power for short-term gain. Again, nature is a silent witness to the contamination of the environment.

Swindling of One Million Years

Healthy fingers and

dreaming hands

extend toward the expanding meadow of

dandelions and lotus. . . . . . . . . . .

For the sake of your prosperity

of the next several decades,

haven’t you swindled one million years

from the Japanese archipelago?”. . . . . . . . . . .

The last stanza echoes the first:

The winds of prayer

blow quietly

through the Japanese archipelago

from the north and the west

in our heart, and

on the wordless field of life

of nuclear contamination

where the dandelions and the lotus spread.Last November on a bright, blustery day, I traveled south along the coast of Fukushima prefecture by train and bus as far as Soma. The Soma region is famous for horse-breeding and a 1000-year old festival known as “Soma Nomaoi,” or wild horse chasing. It is also just 30 miles north the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. I had trouble finding a room, as hotels were full of temporary workers hired to decontaminate areas in the “nuclear exclusion zone.” Poet Hiroshi Suzuki calls the clean-up efforts a “disguise” and points out “swindlers” who profit from the disaster and cover-up “the real dirt.”

Decontamination

They eliminate the surface soil and wash the walls and roofs.

That is the disguise called decontamination.

Where can we flush away things

that will never become clean

in twenty thousand years?. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Where does the real dirt lie?

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

We see swindlers everywhere.

Only our courage to stand up to them

can begin to decontaminate the real dirt.The final two excerpts are from two poets, both born in Fukushima, who reflect on nature’s bounty and the sorrow of losing their homes and way of life that moved in rhythm to the seasons. In “To My Home,” Setsuko Okubo affirms, “Our prime blessing is brought by the soil..inherited and guarded.” In the first and last stanzas, the repetition of the names of wild plants they used to gather serves as a litany.

To My Home

Butterbur sprouts, five-leaf aralia, fatsia sprouts, bracken, and parsley.

When the mountains are ready

for the sprouting of plants,

the rice fields are dug, and the fields are cultivated,

calves are born,

horses are pastured,

and chickens lay eggs.

It’s a season full of life.

In the fall

Ears of rice rustle.

The smell of rice heralds the harvest.. . . . . . . . . . .

Then, “In a twinkle it vanished../ life-taking radiation —/ contaminated my home”

We had to slaughter the cows that we had tenderly watched over.

We abandoned our racehorses that we had raised with the utmost care,

left our houses, fields, and livestock, and evacuated.

We drift from shelter to shelter as refugees.. . . . . . . . . . .

Spring has rolled around again.

Butterbur sprouts, five-leaf aralia, fatsia sprouts, bracken, and parsley.

They are waiting to be picked

on the desolate land.Chihiro Uozumi movingly paints a picture of the beauty of her home on the coast of Fukushima, and the soul’s longing for what was taken by the nuclear accident — “a scream of excess.”

The Place Where the Soul Flies

There was a broad sky.

There was a deep blue sea.

A snowy white sand hill spread out, and deep green pinewoods grew thick.

The place where I was born and raised

was a quiet coastal town,

a place where the soul flies.. . . . . . . . . . .

On that day,

Was it a cry or a scream of excess?. . . . . . . . . . .

That path

terminated in the sea at Fukushima

and brutally exploded.. . . . . . . . . . .

The final stanza echos the first:

There was a broad sky.

There was a deep blue sea

My hometown

is still the place

to which my soul returnsKudos to the editors – Leah Stenson of Portland and Asao Sarukawa Aroldi of Tokyo – for selecting and editing these fifty poems and bringing Reverberations from Fukushima to life. The collection more than meets their goal to “open the eyes of the American public to the dangers inherent in uranium-based nuclear power” and “enhance Americans’ knowledge of contemporary Japanese poetry.”

Inkwater Press is to be commended for undertaking the publication of this bilingual collection – open the book at the front to read the poems in English, open at the other front to read the poems in Japanese, or at last admire the neat, vertical script! Learn more about Fukushima – the land, the people, the nuclear accident, what’s happening today. http://fukushimaontheglobe.com/

Reviewer Bio: Ruthy Kanagy is the author of “Living Abroad in Japan” (2013, Avalon Travel Publishers). Her poems have appeared in Fault Lines Poetry and Eugene 150th Birthday Celebration Poetry Collection. A native Tokyoite living in Eugene, she is mostly retired, loves to hike and travel with her bike, and leads Japan Cycle Tours annually.

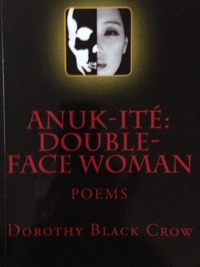

Anuk-Ité: Double-Face Woman by Dorothy Black Crow, reviewed by Carter McKenzie

December 2, 2014Review by Carter McKenzie

Anuk-Ité: Double-Face Woman, Poems

By Dorothy Black Crow

Turnstone Publishing (Corvallis, Oregon)

ISBN: 9781479338580

2012, 39 pp., $9.90 (on Amazon)

dorothyblackcrow.com The poems in Anuk-Ité: Double-Face Woman by Dorothy Black Crow demonstrate the skill and wisdom of balance; through deft understatement they achieve the resonance of cumulative effect: they are weavings of one who knows how to reach into potent mystery “steady not pierced / by the black barb.” (“Double-Face Woman”)

The poems in Anuk-Ité: Double-Face Woman by Dorothy Black Crow demonstrate the skill and wisdom of balance; through deft understatement they achieve the resonance of cumulative effect: they are weavings of one who knows how to reach into potent mystery “steady not pierced / by the black barb.” (“Double-Face Woman”)Manifested through the physical and spiritual worlds, and informed by Lakota history and legend, these poems honor and explore the possibilities of familial interconnection even as they expose betrayals of a people. With the exception of one well-placed villanelle, the poems are narratives. They all bear witness in memorable ways both to a Lakota history of suffering and to the authority of survival and renewal. In the light of carefully crafted language, silence becomes fiercely active: omissions become revelations.

In “Marriage Proposal at Branding Iron Creek #1,” the dwelling place consisting of a “metal cot beyond the black / iron woodstove” is marked by the violence of the past, an “M-16 bullet hole / clean through the foot-wide cedar log.” The understatement of the second stanza, “ ‘They got their man, Peltier, in jail,’ ” in its reference to the 1975 Pine Ridge shootout and to the injustices that preceded and followed it, only deepens the impact of the scene created in the first stanza. Yet details in this poem also reveal the care of the past: “the faint glow of whitewashed log / cabin walls axe-planed smooth long ago.” And, although “old vision pits / crumble in Badlands shale” in the surrounding land, the calls of Spirit owls persist. The speaker identifies herself as having been an outsider to this world in the poem’s epigraph “Can I Live Here?,” as well as through the context of the poem that precedes this proposal, “Christmas at Upper Cut Meat.” That the answer to her question is affirmative is shown in what she notes beneath the spider webs over the open door: “red tobacco ties still bless this place.” Spiritual power actively recalled through attentiveness makes possible inclusive partnership.

Central in Anuk-Ité are poems of recovery and transformation through prayer. “Wind Cave I: Inside Grandmother Earth’s Lungs” and “Wind Cave II: Time of Emergence” evoke the Lakota creation story of their Buffalo Nation, and the shape-shifting power of recovery. The first poem concerns appropriation that disconnects the cave from its spiritual meaning for the Lakota of being the first people’s entryway to the earth’s surface. Here, the Black Hills journey into the interior of the famous Wind Cave is no more than voyeuristic tourism, unconscious violation for the sake of curiosity. The entry is a door “blasted” in the side of Grandmother Earth, and the cave is “songless, / speechless.” Those who wander into the cave do so without reverence: “Like a virus / we swarm the lungs, / creep past the silence…penetrate / dry air pockets” where there are “no / air sacs / left; / nothing.” Lack of attention to the sacred in this context has taken away the breath needed for the vitality of a people’s place of origin. In this poem, loss of vision is the loss of the entryway to the sacred center’s mystery. The lungs of the cave are lifeless.

In contrast, “Wind Cave II” resurrects the sacred power of place by remembering the stories of origin and disappearance, the buffalo that “sank into earth” after being slaughtered for their tongues, and who were said to have gone into hiding in caves, “waiting without grass, hooves / still in the rock.” The association of the earth and the buffalo with the Lakota people lies in a shared lineage “some say” exists: “the soft red rock… / is the blood of Mother Earth / is the blood of First People / is the blood of Mammoth Bison.” Regarding the Buffalo Nation, this speaker states: “When we rise up from the earth again / we will not need the stairs.” Certainty is declared through faith: “I know the Place of Emergence: / Center of All That Is— / this time, Wind Cave.” Consciousness of the sacred—recognition of what is possible in “this time”—becomes the location of the opening to the center that will hold.

The sharpness of details and subtlety of their placement throughout this collection of poems resemble the artistic power of quillworking that Anuk-Ité bestowed upon those women who dared to dream fiercely enough to withstand her gift, enabling them “to pull out all those designs / pricked in the night sky — / quilled whorls and stars —.” (“Double-Face Woman”) This poetry’s honoring of Native American wisdom is a gathering of voices that renews connection, sustaining an essential fire.

Reviewer Bio: Carter McKenzie’s work has appeared in a number of anthologies and journals. She is the author of the chapbook Naming Departure and a full-length book of poetry Out of Refusal. A founding member of the poetry collective Airlie Press, Carter teaches poetry sessions to children and adults in Eugene and in the surrounding rural areas and serves as a board member of Beyond Toxics. She lives with her youngest daughter in the Cascade foothills.

High-Voltage Lines by Tiel Aisha Ansari, reviewed by Lois Rosen

November 8, 2014High-Voltage Lines

by Tiel Aisha AnsariBarefoot Muse Press 2012

ISBN-13:978-615663760

Paperback: 40 pagesTiel Aisha Ansari’s poetry collection, High-Voltage Lines, lives up to its name. Like the conduits delivering strong electrical charges, sparking the air around them, her artful lines convey potent messages. Tiel treats the reader to a dazzling array of well-crafted formal verse poems including villanelles, pantoums, ghazals, sonnets, and sestinas. Her work is a tour de force of metrical and syntactical dexterity that delights the reader with its skilled blending of structure and meaning.

The collection’s first poem immediately invites us into a world of erudite fun:

The Author Introduces Herself

Phrenologue dialogue:

Doctor O’Quackery

says that my cranium

shows I am dull.Lethally boring, the

un-entertaining-est

gal in the world, by the

bumps on my skull.The narrator asserts she is “dull,” but the bouncy rhythm and high-level of language shown by such words and “cranium” and “lethally” as they contrast with silly, invented words like “O’Quakery” and “un-entertainingest” belie this message. She welcomes readers to a world of intelligent craft and word play.

The poetic landscape throughout the book is rhymed verse in set forms, but what might seem sing-songy or old-fashioned written by someone less adept, becomes fresh, lively and evocative in Tiel’s hands. Her pentameter lines remind me of Shakespeare.

Her compassion, spiritual reverence, concern for the nature, and humanity shine throughout this collection. Her literary knowledge allows her to re-imagine characters such as Edmund and Edgar from King Lear and Penelope from the Odyssey. The reader of Tiel’s poems gets to join her in zooming in, for example, on what Odysseus’ lonely wife endures in his absence, how Penelope protects herself from “louts… who quarrel over her with foolish boasts.”

Here are the first two stanzas of Tiel’s pantoum, “Penelope.”

Penelope, Ithaka’s lonesome Queen

is weaving web of excuse and deceit

to blind and bind the suitors she had seen

come crowding to her door on hasty feet.She’s weaving webs of excuse and deceit

That she unravels every night, alone.

They crowd into her door on hasty feet

Each morn, to find her work is not yet done.The selection of this form’s line repetition from one stanza to the next in a fixed pattern mimics Penelope’s actions of weaving and unraveling the same threads. The pantoum’s last line is the same as the first. The poem comes full circle just as Penelope’s work does.

The topics in Tiel’s expansive poetry repertoire delve into nature, politics, peace, daily life, news, homage, and her spirituality. David Hedges, president emeritus of the Oregon Poetry Association, describes High-Voltage Lines as “a wellspring of wordplay and wit, a feast of fresh images, a seamless blend of heart, mind, body and spirit.” I enthusiastically agree.

Tiel Aisha Ansari is the current president of the Oregon Poetry Association. She has been a dedicated, generous and gifted leader. This book provides us yet another example of her talent.

Reviewer Bio: Lois Rosen, of Salem, co-founded the Peregrine Writers. Traprock Books published her first book, Pigeons, in 2004. She’s taught ESL at Chemeketa Community College and Creative Writing at Willamette University. Her poetry has appeared most recently in VoiceCatcher, Calyx, Conversations Across Borders, and Alimentum: The Literature of Food.

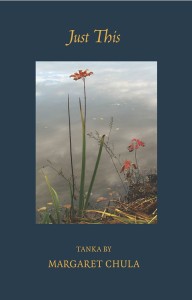

Just This, Tanka by Margaret Chula, reviewed by Penelope Schott

September 28, 2014 Review by Penelope Scambly Schott

Review by Penelope Scambly SchottJust This, Tanka

by Margaret Chula,Mountains and Rivers Press, 2013

92 pages, $16.00Imagine there is someone standing in front of you with a lifted hand and upstretched fingers. Two fingers are presenting a delicate object in order for you to see it clearly. Listen as the person whispers to you, “just this.” In that moment you will look at this single lifted object as if there were nothing else in the world. That’s how Margaret Chula’s poems work.

A tanka, in case you’ve forgotten, is a five-line lyrical poem. The name itself means “short poem” and the form is derived from ancient Japanese verse. Although much shorter, generally 31 syllables or fewer, the tanka works a little like a sonnet with a pivotal turn before the end. Unlike haiku which are generally nature poems, the tanka is more likely to deal with human relations.

This collection of 100 tanka, the classical number for such a gathering, is divided into five titled sections: Lingering Fragrance, Who Can Say What Loneliness Is, Hush of Crickets, Trying to Remember, and Yesterday’s Desire. Four sections open with a tanka by the Japanese woman poet Izumi Shikibu who was writing around 1000 A.D. and one opens with a poem by Ono no Komachi from a century earlier.

The book is dedicated “in loving memory of my mother” and here are the first two poems from Lingering Fragrance, the first by Izumi Shikibu and the second by Margaret Chula.

Wakened by the scent

of flowering plum…

The darkness

of the spring night

fills me with longing.– Izumi Shikibu

late summer

in the garden

just before dusk

touching leaves and flowers

as I never touched you– Margaret Chula

Although Chula writes about lovers, childhood, lost youth, and other subjects, the book keeps circling back to the loss of the mother. Thus her first poem in the last section:

this morning

pale white light

shines through the window

it’s snowing again

and Mother is goneThe poems in this collection are often wistful, but sometimes also humorous:

those five pounds I lost

during my gallbladder attack

where did they go?

fourteen baby chicks

scamper in the sunshineor

displayed in the window

of a consignment shop

my old evening gown

on a flaxen-haired manikin

the size I once wasWhatever the subject, these tanka are consistently evocative. Margaret Chula has lived in Japan and made a study of that poetic tradition. In this moving collection, she has taken the inherited form and successfully made it her own. Each small poem is exquisite in its own way, and over and over as you read, you will quietly see and appreciate “just this.”

Reviewer Bio: Penelope Scambly Schott’s verse biography A Is for Anne: Mistress Hutchinson Disturbs the Commonwealth received an Oregon Book Award. Recent books are Lovesong for Dufur and Lillie Was a Goddess, Lillie Was a Whore. Forthcoming Fall 2014 is How I Became an Historian. Penelope teaches an annual workshop in Dufur, Oregon.